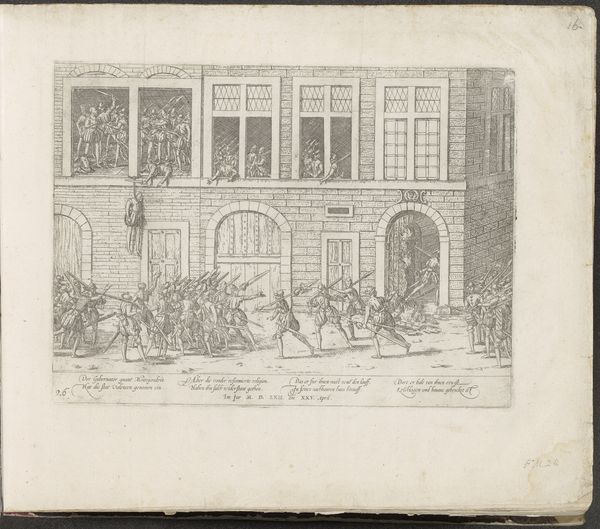

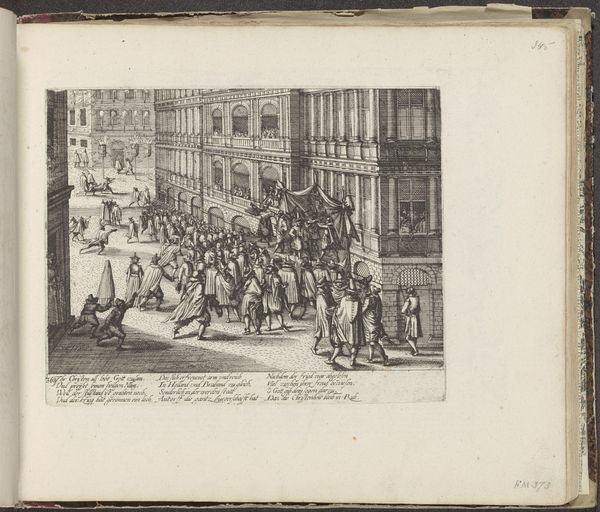

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 215 mm, width 280 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

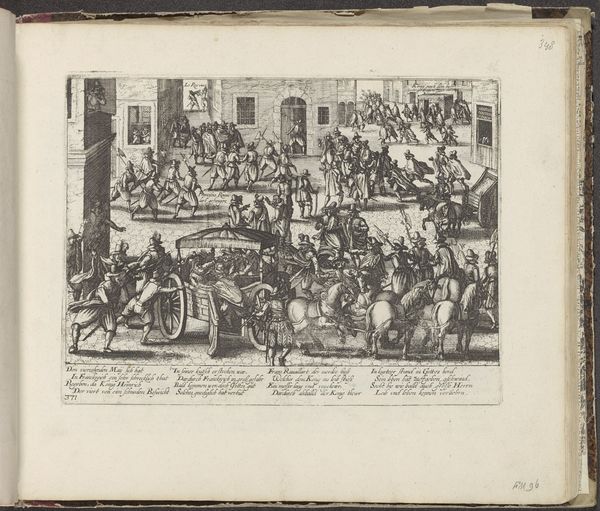

Curator: Looking at this piece by Frans Hogenberg titled "Moord op de gebroeders de Guise, 1588", dating from around 1589 to 1593, now held at the Rijksmuseum, what strikes you first? It’s an engraving. Editor: Well, my initial sense is controlled chaos! All those figures crammed into that space. I almost feel trapped looking at it, like I'm going to get stabbed by one of those pointy weapons. But also, I notice how strangely still everyone is despite the action; it is quite theatrical in nature. Curator: The "controlled" aspect you point out is key. As a print, it was meant for wide distribution, shaping public opinion about a pivotal historical event. The assassination of the Guise brothers was a hugely destabilizing act, so the image functions almost as political propaganda. Editor: Propaganda, huh? Makes you wonder who commissioned it and what slant they were trying to put on things. But you’re right, there's definitely a story being told, even though I don’t know the first thing about the Guise brothers. Look at the way the space is divided—it’s like a stage. Curator: Precisely. Hogenberg’s piece condenses multiple moments into a single scene. We see the Duke being ambushed, and then, lower left, his body being carried away. This collapsing of time speaks to early printmaking conventions but also emphasizes the speed and brutality of the event, the drama of regime change. Editor: And the architecture is so cold and imposing; all that stone really locks them in. The columns add an unsettling formality to the violence taking place behind them. Even the arched entryways appear like judging eyes staring at what is taking place below. Curator: You're highlighting the performative aspect of power. Courtly spaces are reimagined here as theaters of cruelty. And by making it available as a relatively cheap and reproducible image, Hogenberg democratized the event, making visible what was previously hidden. Editor: Hmm. So it's about making power, and the abuse of it, visible. Something about this still unnerves me, it feels so...calculated. Curator: Yes, it's a visual articulation of raw political power. After reflecting on this piece, I feel a greater connection to the visceral reality of 16th century statecraft, and how deeply enmeshed imagery was in shaping and reshaping historical narratives. Editor: For me, it is more the lasting reminder that even the grandest stage, the most ornate structure, is easily defiled with a little bit of bad intent. And the horror of that I will carry with me long after moving on to the next artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.