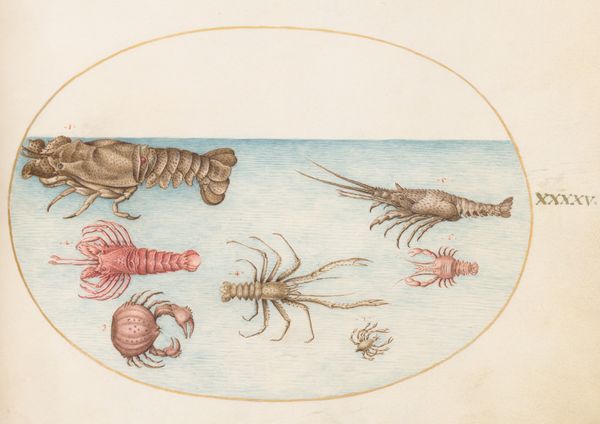

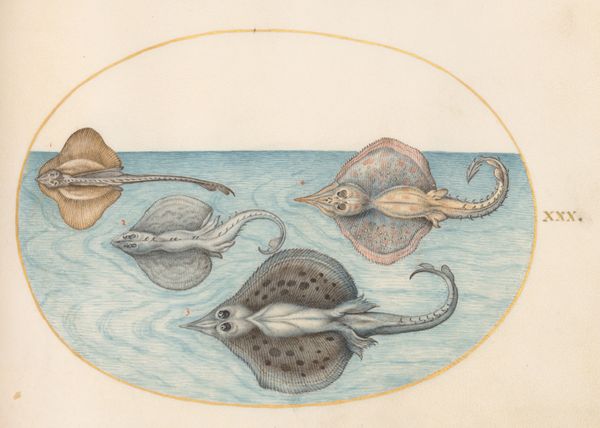

Plate 50: A Dead Hermit(?) Crab with Tower Snail Shells c. 1575 - 1580

0:00

0:00

drawing, coloured-pencil, watercolor

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

mannerism

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolour illustration

#

miniature

#

watercolor

Dimensions: page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

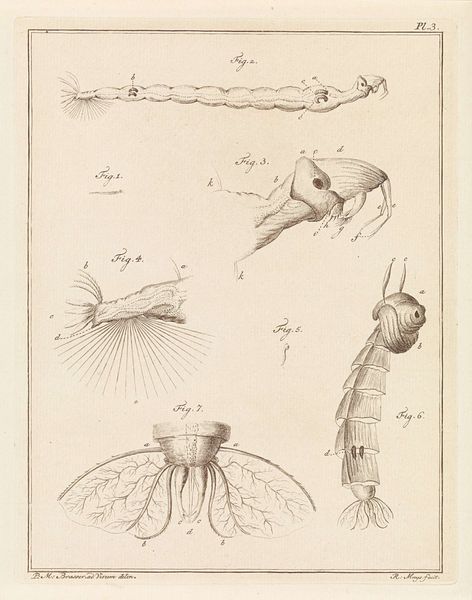

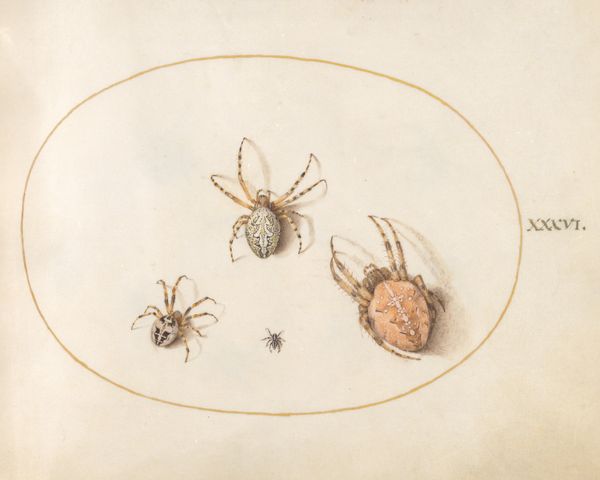

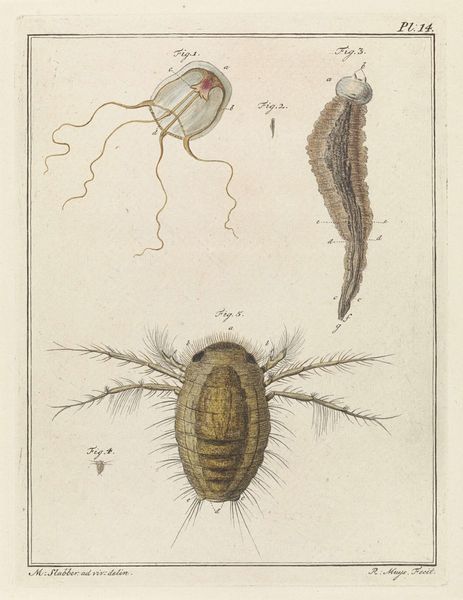

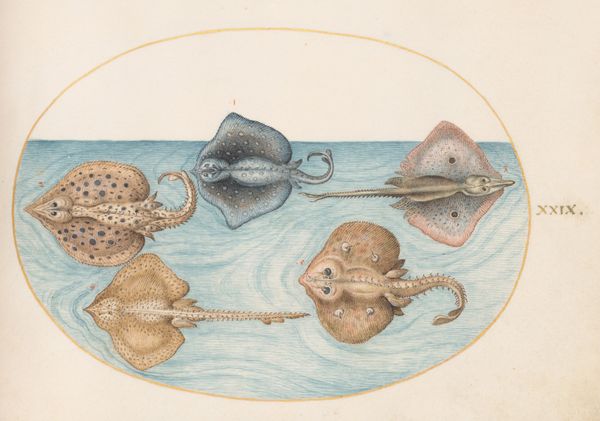

Curator: Joris Hoefnagel's "Plate 50: A Dead Hermit(?) Crab with Tower Snail Shells," created around 1575-1580, presents a fascinating study in miniature natural history. The artist employs watercolor and colored pencil to capture the intricate details of these specimens. Editor: My immediate reaction is that there's a quiet stillness to this composition, a sort of elegiac beauty in these humble marine creatures. The artist meticulously records the textures of the shells—the dots, ridges and colors... What interests me, though, is that crab's little pink bow on the forehead—a detail seemingly disconnected from the "realistic" scene... Curator: Indeed. Hoefnagel was a master of observation. This plate comes from a series that highlights both his scientific curiosity and a Mannerist sensibility. The artist doesn't just record nature, he arranges it. The placement of the crab and shells, along with those hand-written numberings next to each specimen, evoke a sense of categorization and human control over the natural world. He transforms nature into a cultural artifact. Editor: The artist certainly paid careful attention to the shells themselves. We might want to look into who owned them—whether from local production, how these snails came into his hands and by what kinds of exchanges, so to understand its value within the society and culture from which the art piece emerged. What processes transformed these sea objects into items for display or artistic study? That transition and social impact matter. Curator: Certainly. Moreover, think about the broader historical context—the age of exploration and increased trade that brought new species to the attention of European scientists and collectors. These meticulously rendered drawings weren't just scientific records; they also functioned as symbols of power, knowledge, and possession. The labor to record this kind of natural wonder also connects it to Europe's expanding global footprint. Editor: So, it becomes more than just a study of nature, but an emblem of Europe's encounter with the world... That tiny pink bow on the crab takes on a darker meaning. I’m more convinced that its cute oddness is actually an active ingredient that throws everything else in an uncomfortable and thought-provoking tension. Curator: Yes, those materials and choices say so much. Reflecting on this, I’m reminded of how the act of representing nature is never neutral. It's always shaped by cultural, social, and political forces. Editor: Absolutely, examining the tangible reveals broader systems. These creatures were far more than subjects; they are agents intertwined within history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.