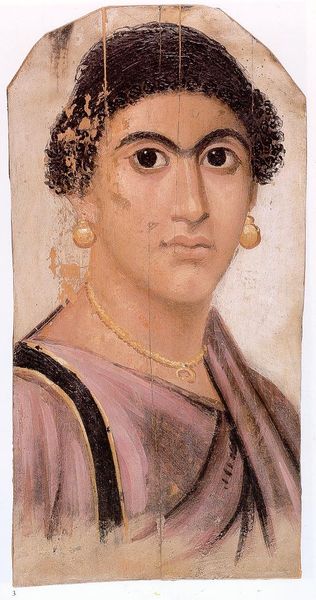

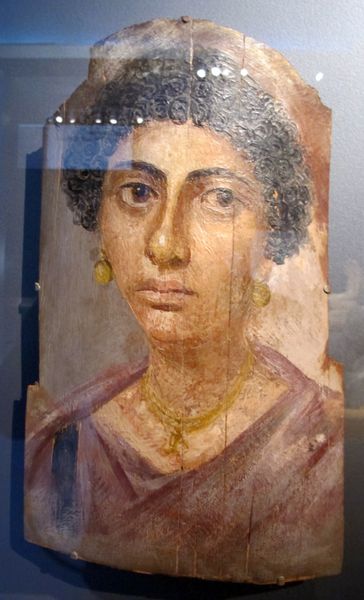

Gayet's Mummy Portraits from Antinoopolis

0:00

0:00

fayumportrait

Egyptian Museum of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

tempera, painting

#

portrait

#

head

#

face

#

tempera

#

painting

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

oil painting

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

portrait art

Copyright: Public domain

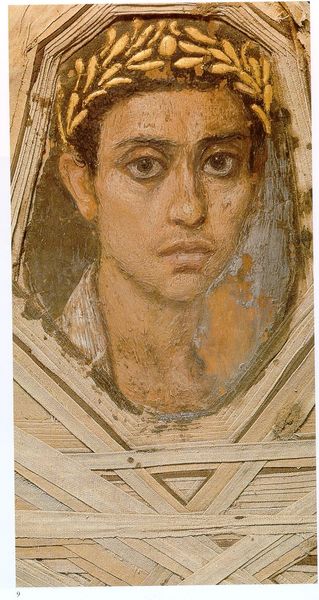

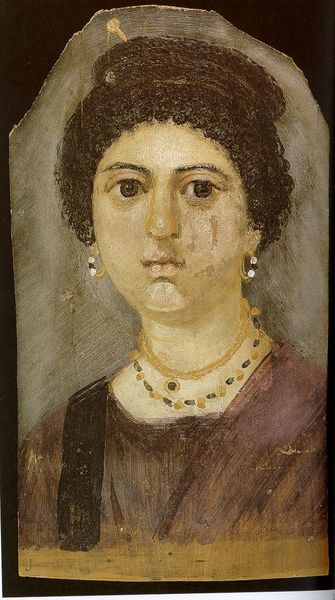

Curator: Before us is one of the "Gayet's Mummy Portraits from Antinoopolis," currently residing in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin. Tempera seems to have been the chosen medium for its creation. What strikes you first? Editor: The eyes. They're incredibly intense, and the gaze follows you. I'm also struck by the layering – the visible strokes, almost a fresco-like quality achieved with tempera. It's remarkably preserved, given its age. Curator: Indeed. Considering the funerary context, it's fascinating to observe the application of tempera. How was it sourced and combined with the raw materials? Also, the wooden panel: its origins and its processing speak volumes about trade networks and artistic production at that time. Editor: The gold leaf wreath is so striking; It frames the face in a way that elevates the subject, bestowing upon them a sense of eternal victory or status in the afterlife. Gold was highly significant, embodying divinity and immortality, something of an optimistic belief about transition from life to the other side. Curator: Precisely! This layering of meaning is further reinforced when you study the support structure – the wood and pigments as commodities. How the application of skill, from panel preparation to the grinding and mixing of materials – what that represents about social and economic conditions. Labor conditions! Editor: Absolutely. Beyond just status, there's a clear Hellenistic influence visible. The wreath, the style of the hair, and the way light plays across the face all point to Roman ideals, merged with traditional Egyptian funerary practices. This intermingling tells a story of cultural exchange and assimilation. Curator: A powerful story embedded in materials. The trade in pigments from afar, the preparation and then use of wood from specific groves—these factors reveal connections we often overlook. The image, the person represented, begins as matter. Editor: Thinking of the figure represented as “matter” brings to mind how ancient beliefs about the soul and body were in transition at the time. Did the portrait serve as a symbolic substitute, or was it believed to embody something more? Curator: Ultimately, both the face and the materials intertwine to speak to history and the individual stories of those who lived it. Thank you for your analysis! Editor: It’s been a privilege delving deeper into this, peeling back the layers of history and symbolism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.