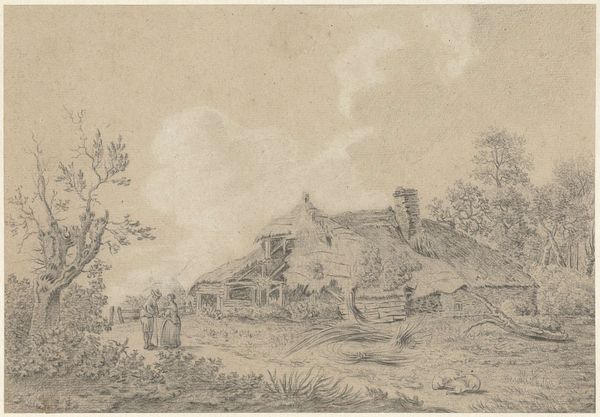

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

line

#

realism

Dimensions: height 151 mm, width 201 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Pieter de Molijn’s "Stenen brug bij een herberg," or "Stone Bridge near an Inn," created around 1660. It’s a delicate pencil drawing currently held in the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It evokes a sense of quietude, doesn’t it? Almost melancholic. The faintness of the lines gives it a ghost-like quality, like a memory of a landscape rather than a literal depiction. Curator: The materiality speaks to a moment of relative peace and prosperity in the Dutch Golden Age. De Molijn wasn’t working with expensive paints and large canvases here, but rather with the easily accessible medium of pencil, implying this drawing was more a study or preparatory work. How do we situate it within the social landscape of its time? Editor: We have to think about what this landscape represents. Bridges, inns... these aren't just features of a pleasant vista. They represent trade, social interaction, possibly even sites of conflict. That humble inn, with its smoking chimney, signifies human activity—a place where people of various social strata might converge. And don't overlook those figures on the left. Are they resting, contemplating their journey? What burdens did they carry? Curator: That bridge itself is so fascinating—a pivotal piece of infrastructure rendered in such a fleeting, almost crumbling, manner. I wonder if the choice to sketch it with such delicate, understated lines hints at the impermanence of human structures against the backdrop of the enduring landscape. Was he aware of how war can impact rural civilian life? Editor: Precisely. De Molijn was creating this image as the Eighty Years' War recently ended. The apparent realism masks a complex web of socioeconomic relations. The very accessibility of landscape art empowered the rising middle class and suggests themes related to ideas of ownership and national identity. We have to ask what it meant to portray the countryside at this moment in history, what social message, if any, lies encoded here. Curator: Indeed, thinking about the materials, the lines themselves were relatively accessible compared to paint pigments and that directly impacts how widely artists and consumers were exploring the rural landscape genre at this moment. And it seems that Pieter de Molijn played a central role in defining that genre at this period. Editor: Exactly. Ultimately, a landscape is never just a landscape. It’s a reflection of society, of power dynamics, and of the artist’s own situated perspective. This seemingly simple drawing is dense with potential readings. Curator: This work underscores the profound ways in which everyday materials can both reflect and shape our understanding of the world, providing insight into production processes, accessibility, and social stratification of art making in Dutch Golden Age. Editor: I’d add, let’s consider the unseen histories and narratives within such bucolic settings. Thanks to de Molijn's humble landscape, we begin to recognize an early chapter in a much longer history still in development today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.