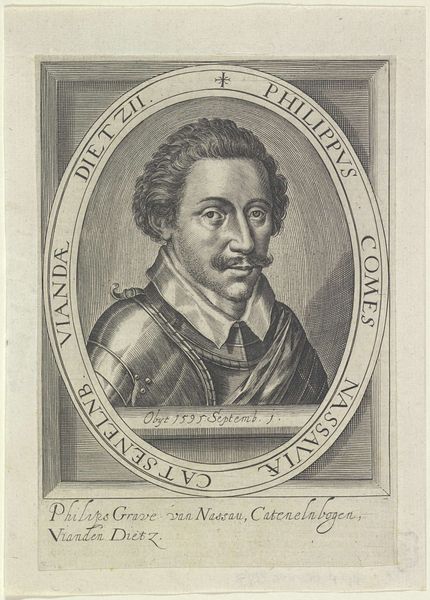

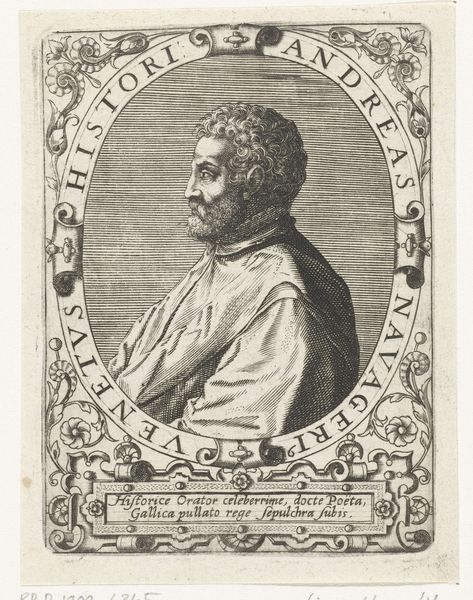

engraving

#

portrait

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

line

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 248 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is “Kindheid,” an engraving made sometime between 1548 and 1570 by an anonymous artist from the Italian Renaissance, here at the Rijksmuseum. I’m immediately struck by the use of line, so precise to render this baby’s chubby face, encircled by that striking geometric border... What's the lasting message, do you think? Curator: Indeed. It captures not just a baby’s likeness, but something more universal: pueritia. Notice the inscription framing the child's portrait: 'Pueritia est Nvm Tener Et Lactans, Pveriq[ue] Simillimvs Avo, Ver Novo,' or 'Childhood is Tender and Nursing, and most similar to the grandfather, in the New Springtime of Life'. What does this return of the origin symbolize, emotionally, do you think? Editor: Hmmm, something about the circle of life? New beginnings echoing old age... But why depict it in this precise, almost stoic way? Curator: Consider how the Renaissance re-embraced classical antiquity. This format—the portrait medallion—draws directly from ancient Roman traditions, where portraiture conveyed lineage and virtue. Even the text's return can evoke this cultural memory, don't you agree? Does that cultural continuity, linking infancy with ancestry, suggest a statement about the hopes for the child’s future? Editor: It's clever how those ancient forms are infused with Renaissance ideals of humanism...It becomes much more than just a picture of a cute baby. Curator: Precisely. This seemingly simple image holds layers of meaning – the innocence of childhood, the weight of history, the cyclical nature of life itself. It serves as a potent symbol, encapsulating both individual potential and cultural legacy. Editor: I hadn’t thought about it that way. The artist transformed something personal into something truly timeless, using those geometric patterns to tie it all together. Curator: And that is the power of symbols!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.