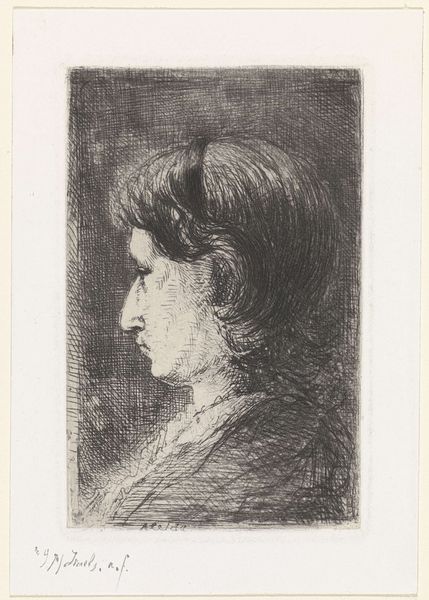

drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

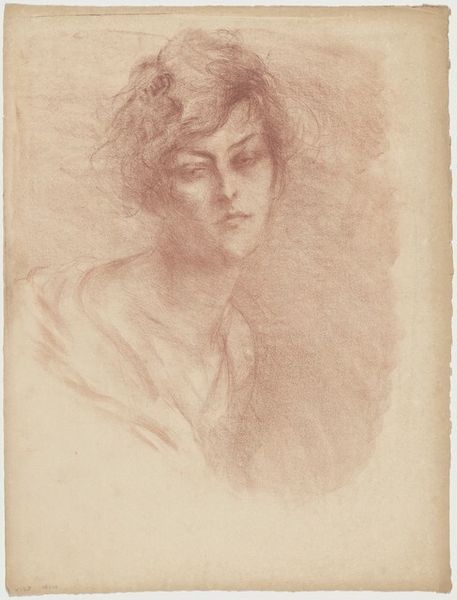

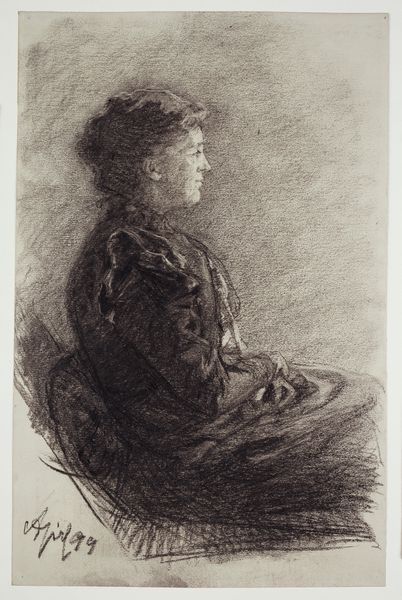

drawing

#

cubism

# print

#

etching

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

modernism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at Jacques Villon's "Miss Bea," created in 1934, one is struck by the artist's masterful use of etching to render a portrait that feels both intimate and enigmatic. What's your immediate reaction to it? Editor: I find the work haunting, actually. There’s a fragility suggested by the linework and the subject’s gaze that resonates even now. It almost feels like we are looking through time into the gaze of a person silenced by history. Curator: Indeed. Villon, brother to Marcel Duchamp and himself a significant figure in the development of Cubism and Modernism, here employs a more subtle application of his stylistic tendencies. Consider the broader artistic context of the interwar period. The image feels more human and less like an object than the high modern works from the turn of the century. What could "Miss Bea" represent within this turbulent social and political context? Editor: Absolutely, it brings up questions about female representation. This image was produced at a time when traditional gender roles were being renegotiated yet simultaneously rigidly reinforced. Is she an embodiment of those tensions, of a woman caught between expectations and aspirations? The very sparseness and lack of defining context allows for projection. Curator: It's compelling how the ambiguity invites multiple readings. The etching as a medium is interesting, because its relatively cheap, which democratized art. This piece's creation occurs within the emergence of consumer culture in Europe. "Miss Bea," as a reproducible image, gains cultural traction through prints, impacting art and social trends. How would this work relate to these issues of class and gender at the time? Editor: I think we also have to see how a "Miss Bea" is a bourgeois subject, whose ability to exist for art says as much about the work's ability to explore its class-based ideas about art, visibility, and social value. "Miss Bea" almost represents the system of her existence as a figure. Curator: Ultimately, Villon’s portrait serves as a poignant study in human expression, and through the intersection of cubist and modern elements, along with social contexts and feminist lenses, we unveil how a seemingly simple image resonates with questions of visibility. Editor: It speaks to the enduring power of portraiture—and the ongoing conversation surrounding who gets to be seen and how they are remembered, critiquing gender, representation, and the silent witnesses etched in lines across history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.