photography

#

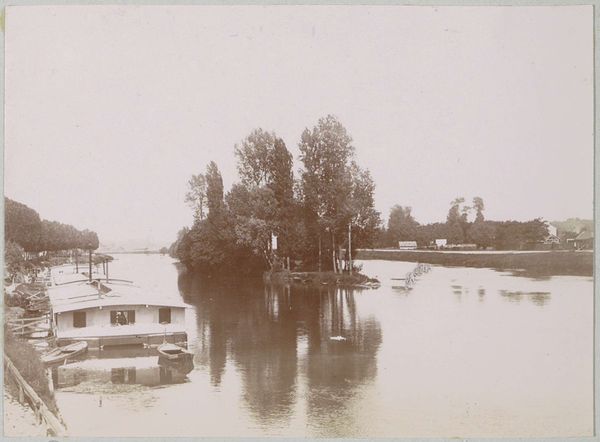

landscape

#

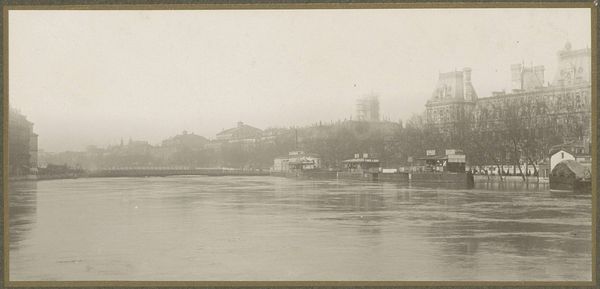

photography

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

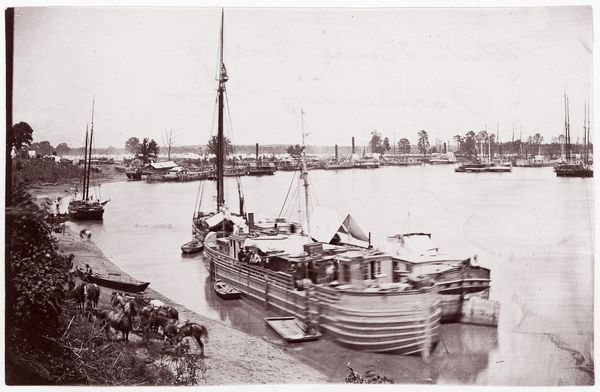

Editor: Here we have Hendrik Doijer's photograph, "Waterkant Paramaribo," taken sometime between 1903 and 1910. The sepia tones give it such an aged feeling, and I'm struck by how still and quiet it seems, despite being a cityscape. What catches your eye when you look at this, considering its time and place? Curator: The means of photographic production are key here. This image captures Paramaribo at a crucial juncture. Photography itself, as a technology, was deeply entwined with colonial administration and resource extraction. The albumen print, for instance, utilized egg whites – a raw material – to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper. How does that connection to raw material shift our perception? Editor: That's fascinating! So you’re saying even the photograph itself is tied to colonial economies? Curator: Precisely. Think about the labor involved: from the photographers documenting the landscape and its resources, to the local population often forced into labor related to these industries, visible or not in the final image. How did the availability and cost of materials and equipment shape photographic practices in a colonial context? What aspects of Paramaribo are emphasized or omitted due to the limitations or biases inherent in the photographic process and the colonial gaze? Editor: It sounds like this photograph isn’t just a picture of a place, but it’s also a record of the material conditions and the power dynamics of that time. It makes me think differently about even seemingly simple images. Curator: Exactly! It’s about tracing the connections between art, materiality, and social structures. Examining those relationships reveals the complex network that shapes not only what is represented, but how it’s represented. Editor: Thank you! Now I have a new appreciation for it!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.