Copyright: Public Domain

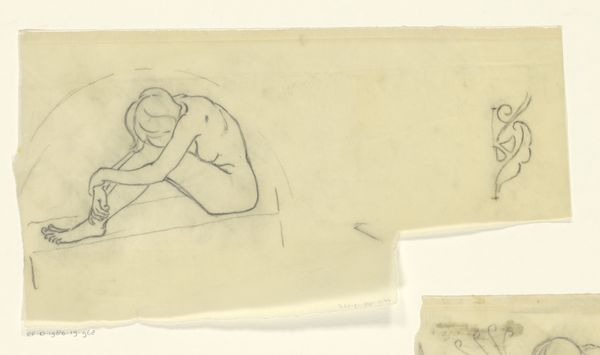

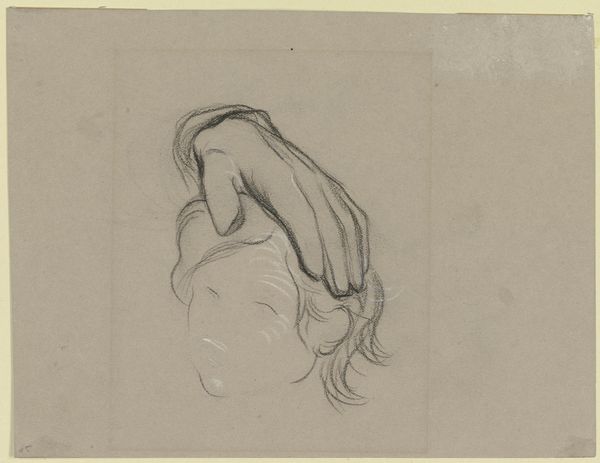

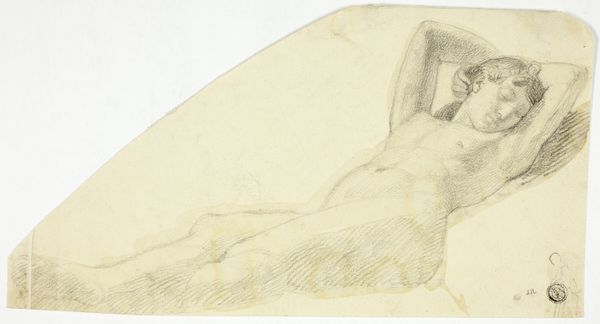

Curator: The Städel Museum holds this arresting drawing by Victor Müller: a "Head of the _forest nymph_," executed around 1862. Editor: It has such an ethereal quality, almost as if the nymph is a fleeting thought captured on paper. There is an incompleteness here that invites the viewer to piece the story together, as though it's been forgotten, or a story we can no longer see. Curator: Quite so! The work is an exemplary instance of Romanticism’s preoccupation with mythological beings and emotional interiority. In this era, it’s striking, particularly how this figure is seen in relationship to nature and how her existence reflects a kind of resistance to industrial expansion. Editor: Exactly. Notice how Müller uses delicate pencil lines, almost whispering her presence into existence. The simplicity, the softness, it rejects the grand narratives of power and authority dominant in state-sponsored art during the 19th century. Is she free, lost, or something in between? Curator: I would like to offer you some perspective. Nymphs in art are nearly always deeply rooted in historical narratives. The figures recur to embody ideals related to purity, the feminine and of the beauty to the extent of symbolizing something far away that we cannot obtain, so one should notice in that epoch these visualisations provided not only pleasure, also became symbols. Editor: So she becomes more than just a beautiful figure—she becomes a symbol for anxieties tied to shifts in societal structures? Curator: I couldn't agree more. It's why artworks such as Müller’s remain so poignant. I feel a deep ambivalence here that reflects the tensions and hopes of an era grappling with profound transformation, but perhaps that is one meaning. Editor: Or, perhaps a symbol that always mutates? Curator: Indeed! We can now return to her form for another symbol search.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.