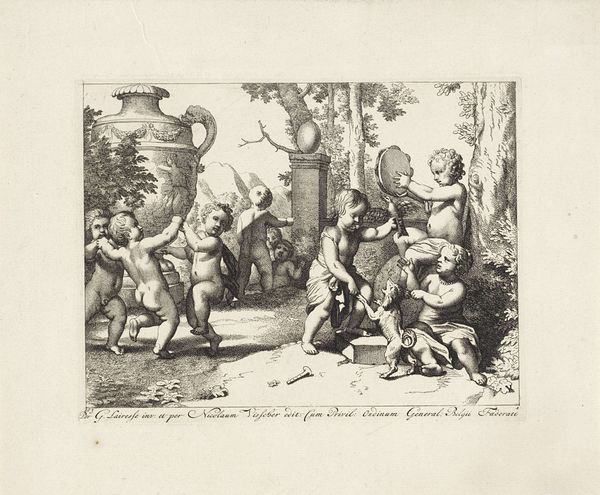

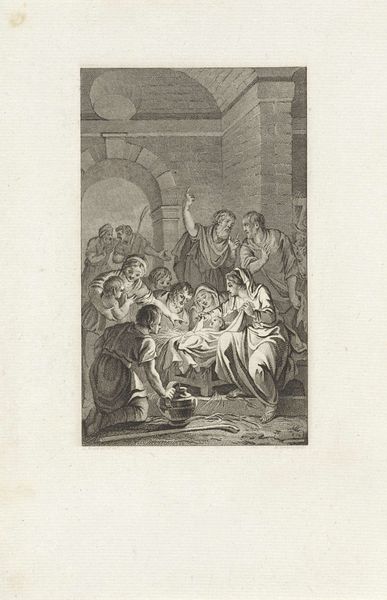

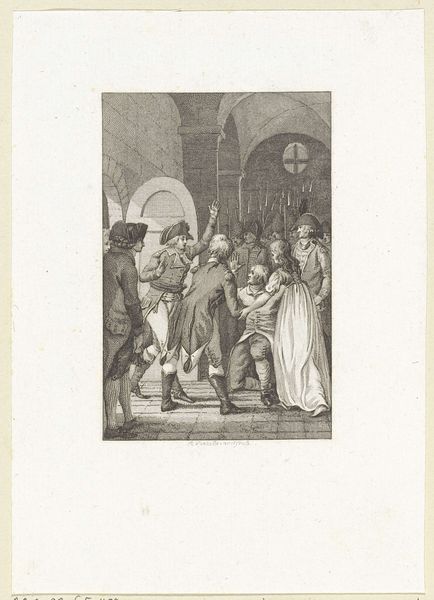

Dimensions: height 251 mm, width 169 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Johann Wilhelm Kaiser's "Spelende Kinderen," placing us sometime between 1823 and 1900. It's a print, a drawing using pencil and engraving, showing a lively group of children playing. The details in the rendering are amazing. How would you interpret this work? Curator: As a materialist, I'm drawn to the processes of reproduction evident in this engraving. Consider the labor involved in creating this image, transferring a scene to a reproducible format. What does it mean to capture and circulate this depiction of childhood through printmaking, making it accessible to a broader audience? Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't considered. It does make me wonder about the intention. Was this aimed at families, a commentary on childhood itself? Curator: Exactly. And think about the market for such images. Were they meant to be didactic, decorative, or something else entirely? The mass production of images coincides with the industrial revolution; how did printmaking contribute to evolving ideas of childhood and leisure? Editor: I see what you mean! The very act of creating and distributing this print positions it within specific economic and social networks, almost objectifying "childhood" for consumption. Curator: Precisely. The material reality of its production and circulation reveals how childhood itself was being constructed and commodified. It urges us to look at the very materiality of art, where cultural and historical perspectives merge. How does this alter your reading? Editor: It makes me look at it with a fresh set of eyes, and that is a valuable insight. Thank you! Curator: Indeed. By attending to the materials and modes of production, we uncover rich layers of social and cultural meaning often overlooked.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.