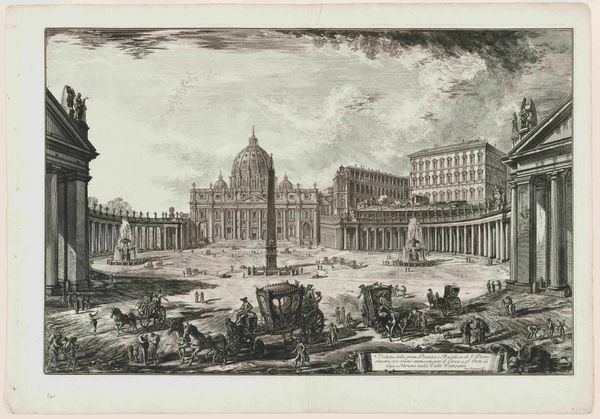

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

cityscape

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 395 mm, width 500 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a print titled “Sint-Pietersplein,” created sometime between 1649 and 1740. It depicts St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City. My initial impression is one of incredible detail. The precision of the lines in the engraving and architecture is breathtaking. Editor: The materiality of the engraving highlights a deliberate and systematic approach. It also brings to my attention that the act of creating the image itself requires tremendous skill, precision and repetition, like bricklaying. Think about the socio-economic dynamics behind this. Who were the skilled laborers crafting this, and what position did their craft occupy in 17th-century Rome? Curator: It is worth remembering that this image emerged in a period when the papacy was actively engaged in solidifying its power and projecting its authority through magnificent architectural projects like St. Peter’s Square, which we can observe in its Baroque splendor, born of the Italian Renaissance. How does this representation then shape, or perhaps control, the reception of the Vatican’s power? Editor: True, these urban-scale projects would require equally grand access to construction materials. Where did the raw materials for the actual architecture come from, who mined the stones, and what were the labor conditions? The very land is appropriated for this expression of power and this print becomes part of that production. Curator: Precisely, consider the symbolic significance. The vastness of the square, the colonnades embracing it… everything communicates a sense of the Church's encompassing reach. Think about Bernini’s vision for the architecture itself. He aimed to create a space where people could gather and be embraced by the church. The print further disseminates this visual and political messaging. Editor: The labor embedded in every stage—from quarrying and construction to printmaking—becomes almost invisible when presented as a finalized image of divine power. It brings up a broader concern of whether the "cityscape" genre, which we see displayed in this print, is equally part of the legitimization of the built and social environment as any royal portrait might have been. Curator: That’s a compelling perspective. It reminds us to question the narratives these images propagate. Editor: It's a print that makes us reflect on power structures and the act of visualizing them. Curator: A testament to the intersection of art, politics, and material realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.