drawing, print, intaglio, engraving

#

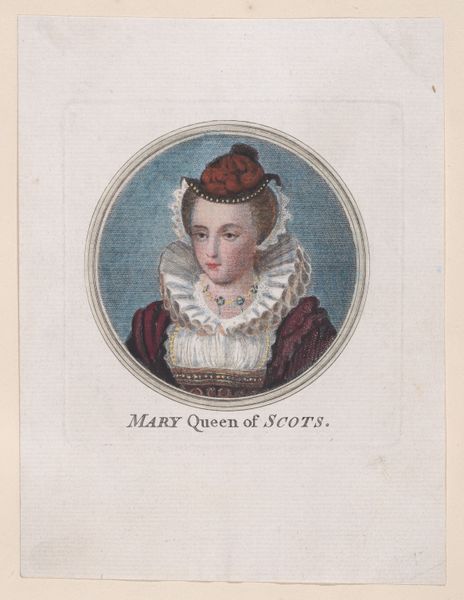

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 4 × 3 13/16 in. (10.1 × 9.7 cm) Sheet: 5 11/16 × 4 1/2 in. (14.4 × 11.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So here we have Charles Townley’s "Mary, Queen of Scots," an intaglio print from sometime between 1770 and 1799. I'm really struck by the starkness of the image, achieved through the fine lines of the engraving. What can you tell me about it? Curator: Well, it's crucial to look at the materials and the process here. Intaglio prints like this one involved laborious handcraft. The very act of engraving the metal plate emphasizes a transfer of power, almost a mimicking of the socio-political hierarchies that defined Mary’s life and death. The materials used—metal plate, paper, ink—were commodities with their own specific economies. How do you think this medium shapes our understanding of Mary's representation versus, say, an oil painting? Editor: That’s an interesting point. An oil painting, at the time, may have had associations with wealth and power, maybe something almost… unattainable? While this print democratizes her image in a way, making it accessible to a broader audience, it's produced using a reproducible medium? Curator: Precisely! The choice of a print suggests wider distribution, hence the question becomes who was its intended audience? This process isn't neutral. The labor of the engraver, the economics of printmaking, even the distribution networks—all contribute to our reading of Mary's story. Consider how the relatively "mass-produced" nature challenges our idea of art with a capital ‘A’ as opposed to a form of accessible historical artifact. Editor: It’s almost like the medium itself carries a commentary on the social and political climate. Looking at it this way really brings to the forefront the kind of historical narratives made available depending on accessibility of art materials. Thank you. Curator: Absolutely! And seeing the material conditions behind it allows us to question what and whom these portraits served beyond mere visual representations. It gives us agency to read between the lines.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.