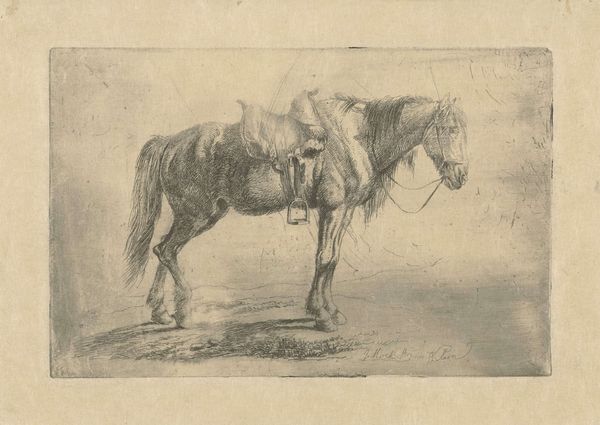

drawing, print, etching, pen

#

portrait

#

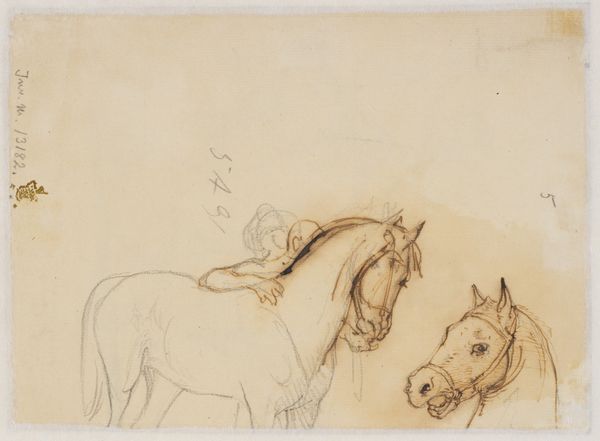

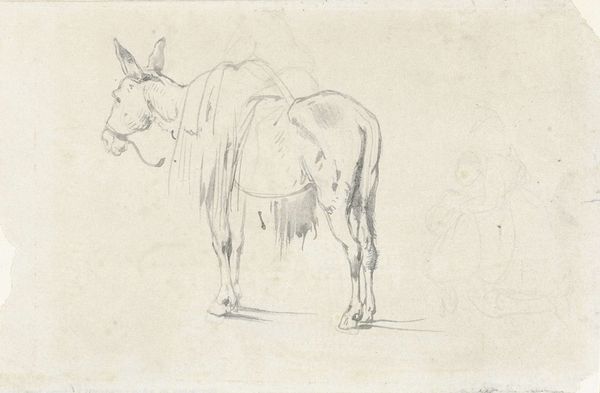

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

romanticism

#

line

#

pen

#

realism

Dimensions: height 74 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

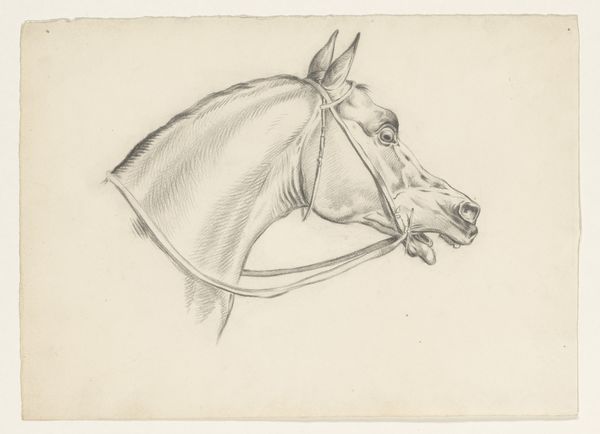

Editor: So, this is "Head of a Horse," made around 1790 by Johann Friedrich Morgenstern. It's an etching, so a print on paper, and I’m struck by how raw and unfinished it looks. There's this detailed focus on the horse’s head and bridle, but everything else is just…sketched in. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: It’s crucial to consider the material processes at play here. Etching, with its reliance on acid and physical pressure, democratized image production to some extent in the late 18th century. Morgenstern, in choosing this medium, made the image replicable, widening its distribution. Do you see how that relates to the subject matter? Editor: I guess…horses were work animals then, not luxury items for most people. Making an image of a horse accessible seems aligned with that everyday function. Curator: Exactly! Furthermore, examine the texture achieved by the etching. The lines, almost frantic in places, mimic the physical strain and the horse’s labored breath. This wasn't just about pretty pictures. It was also a material encounter, representing the working class and their labor. Notice too, how the line blurs between a work of 'art' and something purely functional? Editor: That makes me rethink the "unfinished" aspect. Maybe the rough quality isn’t a lack of skill, but a conscious choice to highlight the material and labor that goes into representation itself, a commentary on the working animal. Curator: Precisely. It pushes against the traditional aesthetic, decentering idealized beauty for something much more raw and, I'd argue, authentic to the historical and social circumstances. Editor: That gives me a totally different perspective. I initially just saw a sketch, but now I see the work as commenting on social issues of labor and the function of representation. Curator: Indeed. Analyzing materials, processes, and the wider cultural and historical contexts transforms how we appreciate this seemingly simple artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.