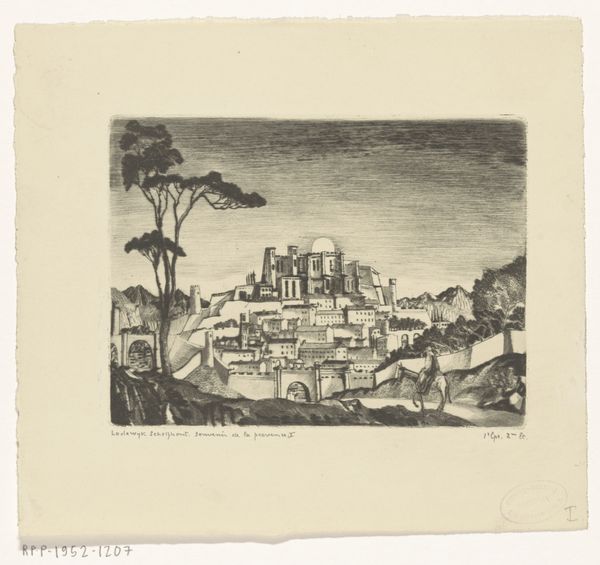

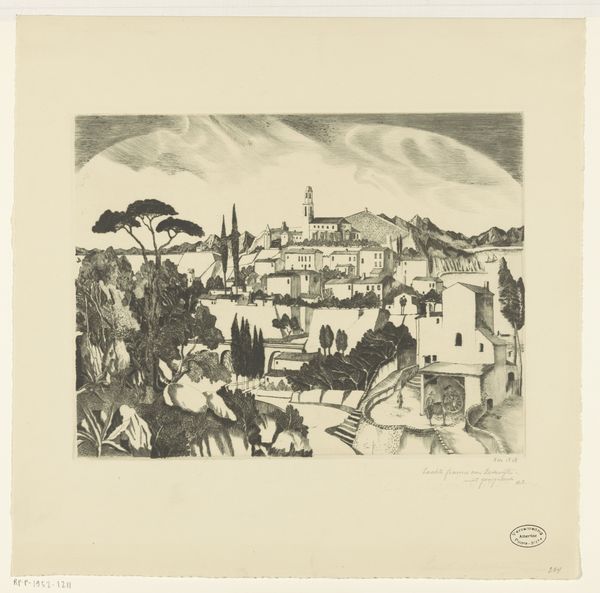

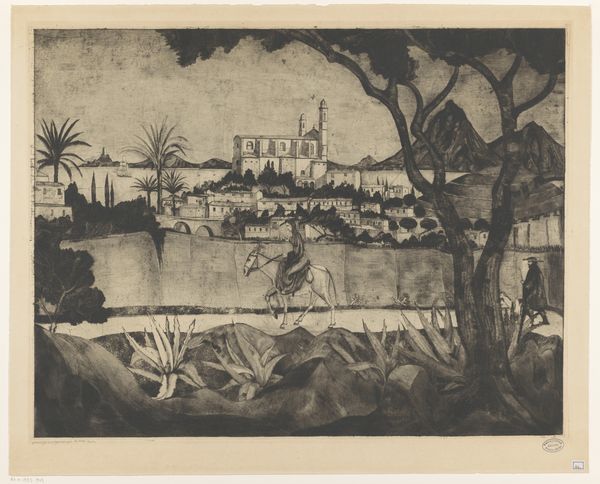

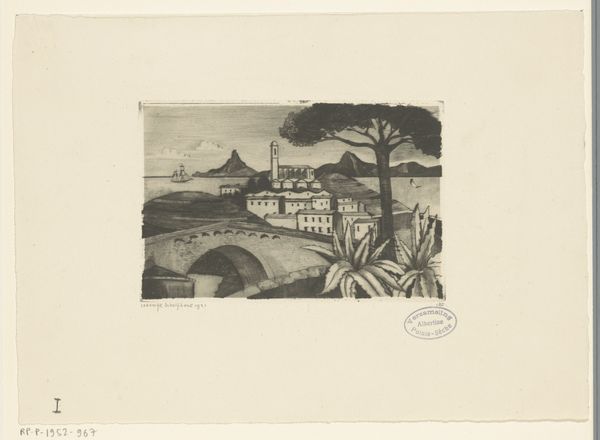

print, etching, paper, ink

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

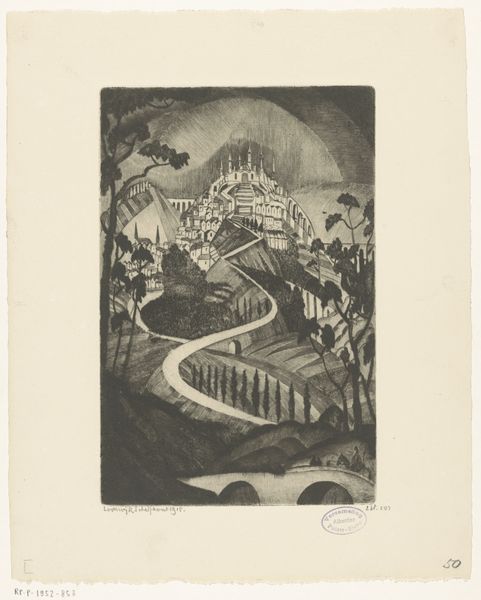

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

modernism

#

realism

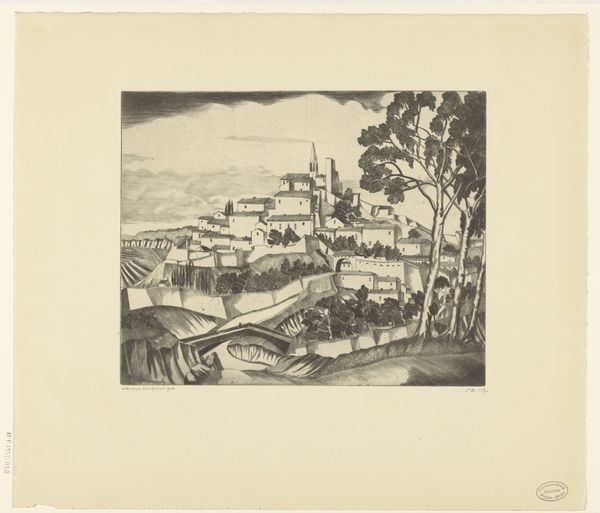

Dimensions: height 497 mm, width 598 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

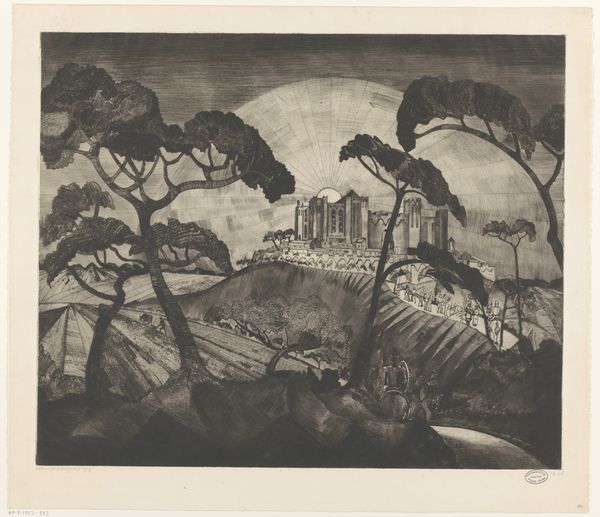

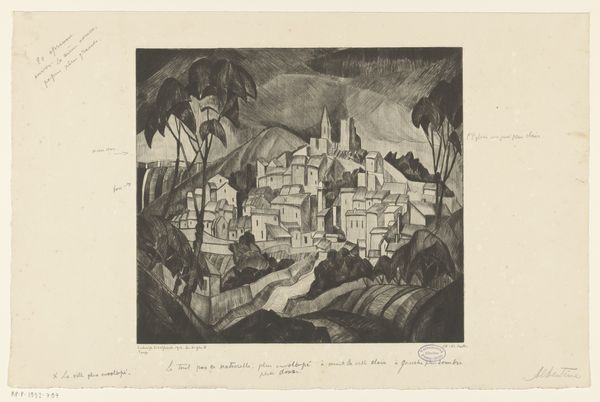

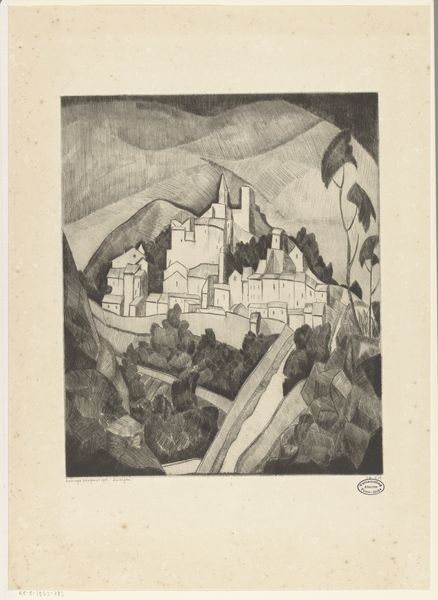

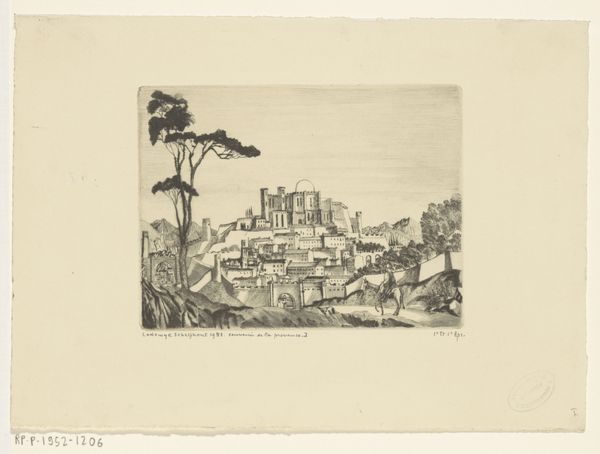

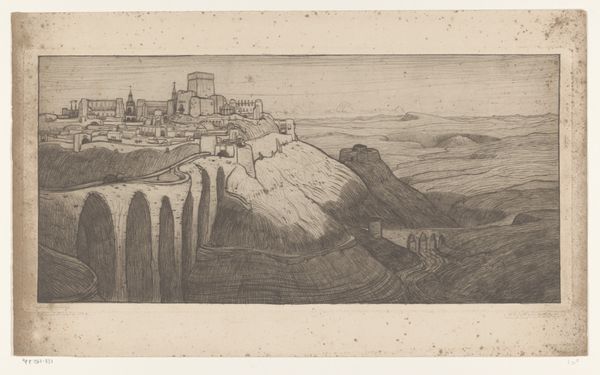

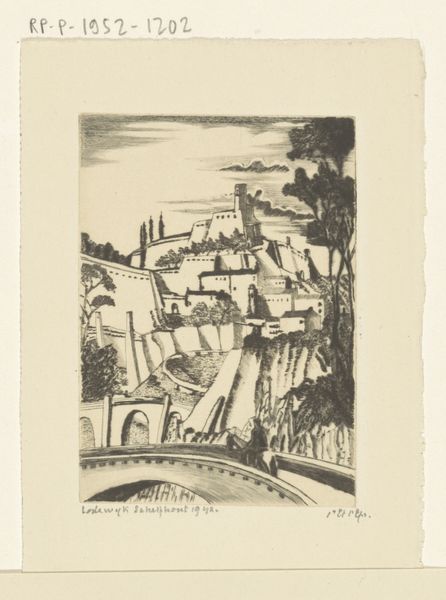

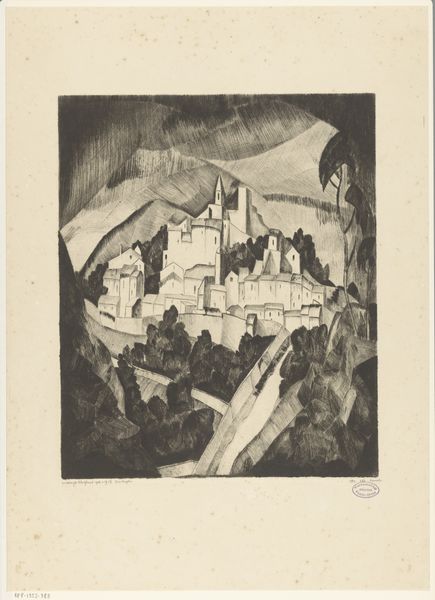

Curator: Lodewijk Schelfhout’s etching and print, entitled “Avignon,” created in 1918. Editor: There's an immediate graphic starkness to this. The sun bursts above a stylized cityscape, it feels both ancient and newly industrial all at once, a somewhat unsettling beauty. Curator: Indeed. Schelfhout, working in the early 20th century, positions Avignon within a pivotal historical context, doesn't he? He uses printmaking – itself a democratic medium – to reimagine traditional landscapes. I wonder what socio-political meanings we might find here. Is this post-war, pre-war? What does this location symbolize in France? Editor: I am curious how the print as a medium here is relevant to our ideas of identity and politics in imagery? Are we talking about the people, are we looking at how they shape the buildings and landscape, or is it something about progress itself. It almost looks geometric. It does seem relevant for after WWI and how we think of this destruction. Curator: Printmaking does allow for widespread dissemination, connecting it directly to the public's access to art and information. Consider the rise of mass media. Are the geometric shapes references to modernist ideals or perhaps hinting at fractured social structures post conflict? The way the landscape is depicted with precise lines might symbolize an effort to rebuild society along rational lines. Editor: Yes, that visual structure gives me some pause. Does it invite accessibility for everyone? If that’s the message, why is there an inherent bleakness that still shines from the piece, if light and day is attempting to move forward through societal constraints? Curator: I think your interpretation hints at a deeper contradiction within modernist projects. A vision that often promoted universality while often overlooking the nuanced experiences of marginalized communities. Schelfhout presents a beautiful image but not necessarily an inclusive one. It encourages dialogue regarding gender, race, and politics because in many ways the beauty is only one dimension. Editor: Absolutely. Considering the political climate and what art becomes afterward, is there some sort of optimism through that message? So, instead of completely feeling like the piece exudes societal constraints, perhaps the print's aesthetic appeal invited discourse on this rebuilding of the mind. Curator: Precisely, that nuanced tension is the piece's power, isn’t it? It's a testament to how artworks become a cultural battlefield for our ideas. Editor: Exactly. Well, that adds another layer for us to discuss while we move into a new chapter. Thank you for these insightful perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.