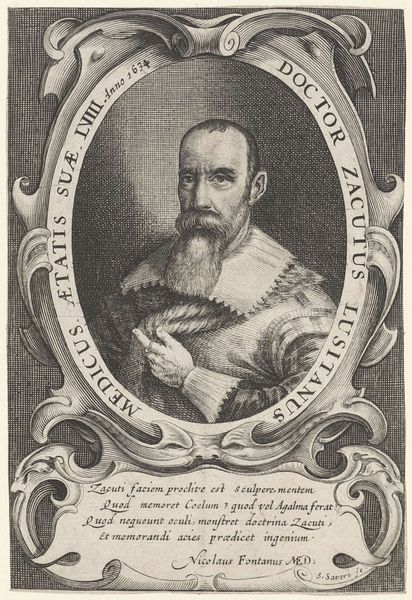

print, metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 302 mm, width 196 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this arresting image! This is a print, an engraving on metal, portraying Ernst van Beieren, Prince-Bishop of Liège. It comes to us from somewhere between 1583 and 1650. Editor: It has a striking severity to it, doesn't it? All stark lines and sharp contrasts, befitting someone with that kind of title. It’s interesting to think about the metal plate and the laborious process needed to achieve this level of detail and these fine lines. It almost mimics the labor of maintaining power, doesn't it? Curator: I see exactly what you mean! The artist, Gijsbert van Veen, seems intent on conveying both power and piety. See how Ernst is framed by an angel holding laurel wreaths, with those trumpets of fame flanking them? A blatant declaration of his virtues, practically etched in steel! Editor: Exactly, but let's consider the cost—literally. Metal was not cheap. Engravings like this weren’t simply artistic expressions, but forms of currency, statements of wealth circulated amongst elites. A subtle message about the prince-bishop's social standing to be bought and displayed. It is fascinating how they translated power into physical artifacts for mass reproduction in Early Modern Europe. Curator: Mass reproduction, maybe within a limited, aristocratic circle, of course! And do not ignore the sheer artistry! Notice the minute details on Ernst’s doublet. It gives texture and vibrancy to what could have been a rather stiff portrait. He’s almost peering out at us. Don't you wonder what he was truly like, behind that formidable gaze and impressive facial hair? Editor: A master of Baroque propaganda! You have a point; however, looking beyond individual brilliance we may begin to wonder if our man of faith felt even remotely connected to his subjects whose exploited labor has indirectly created such luxurious image, even those it meant he was even less divine and certainly less powerful in reality! Curator: It's easy to lose ourselves speculating, isn’t it? But perhaps we should leave our listeners with that very question, about the gap that can exist between an image and lived truth. Editor: Absolutely! Maybe the most intriguing part about the portrait is not just the message itself, but the materials and machinery that sustained the illusion, as it remains a powerful reminder that even divinity, or in this case, noblemen, relied on human and material networks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.