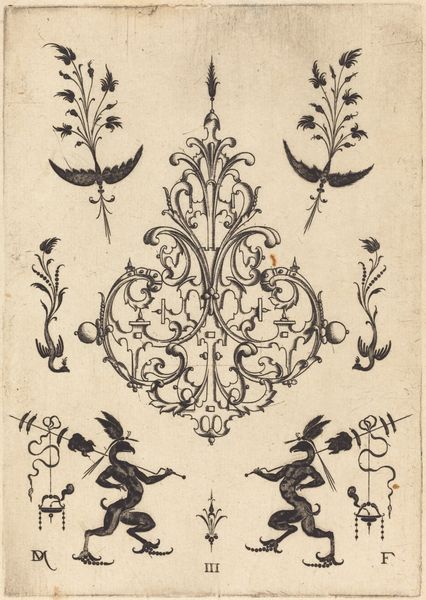

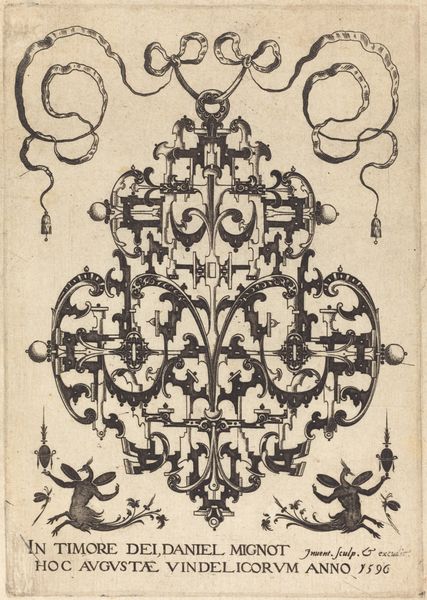

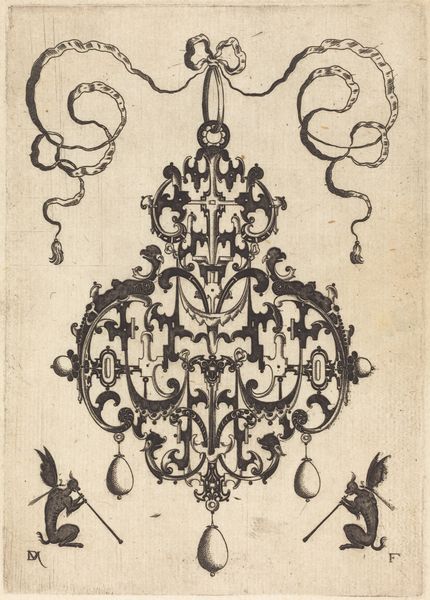

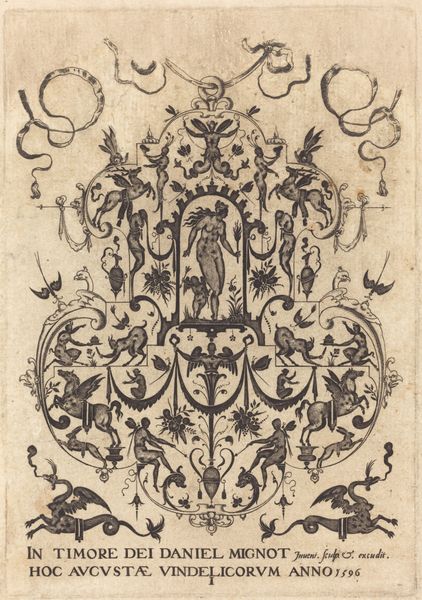

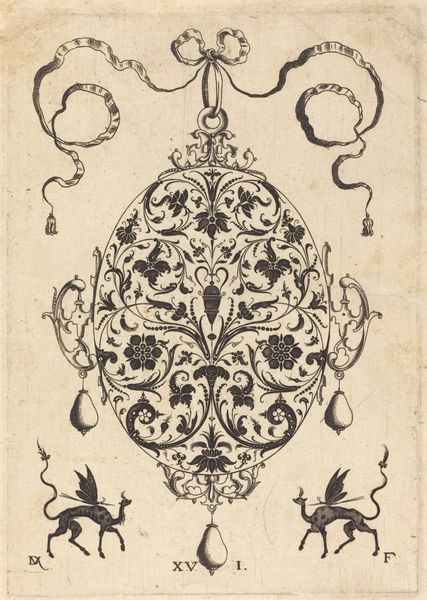

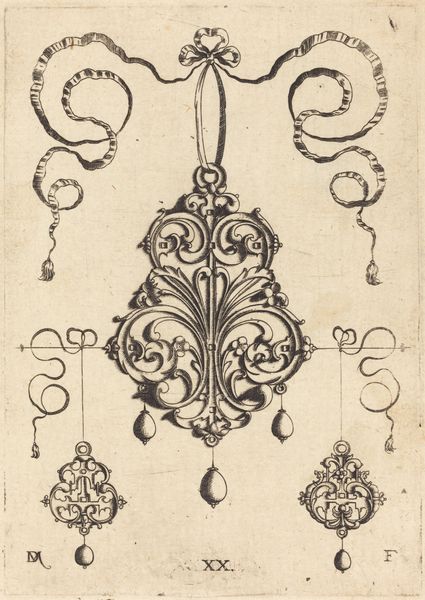

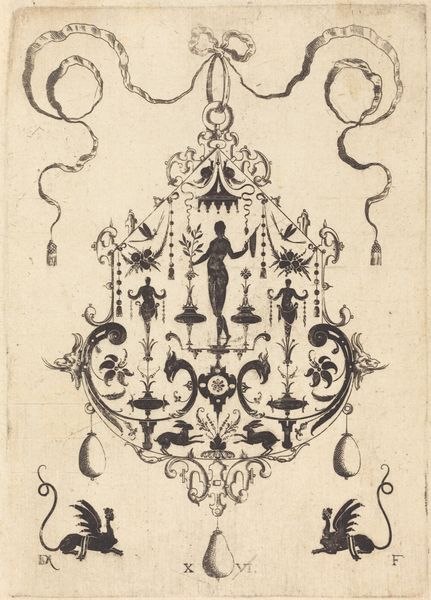

Title-Page: Brooch, Snail-like Animals Above, Centaurs with Banners at Bottom 1596

0:00

0:00

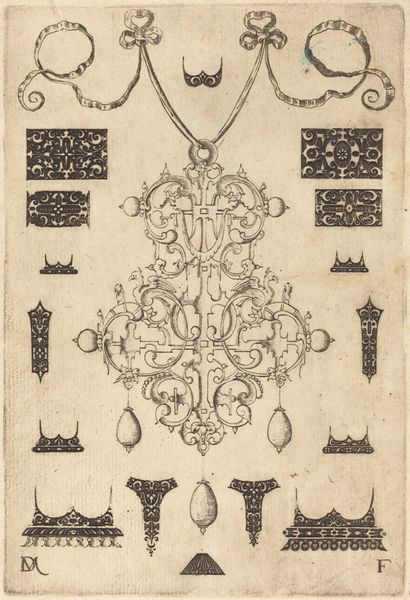

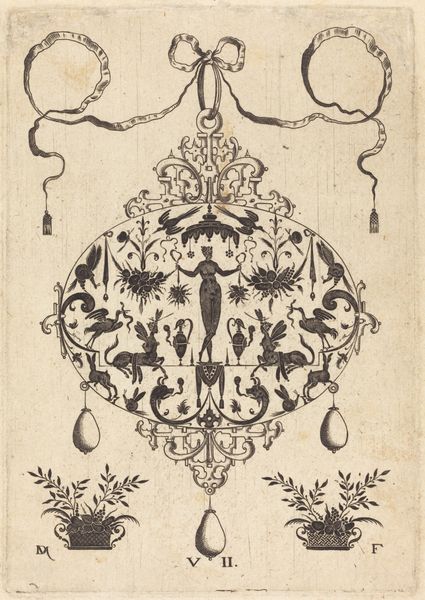

drawing, print, etching, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

ink

#

geometric

#

line

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

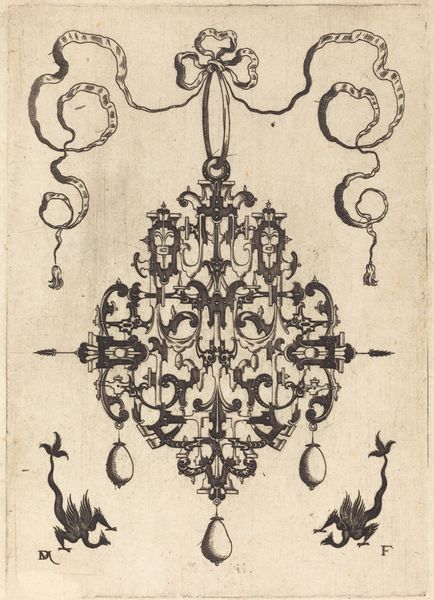

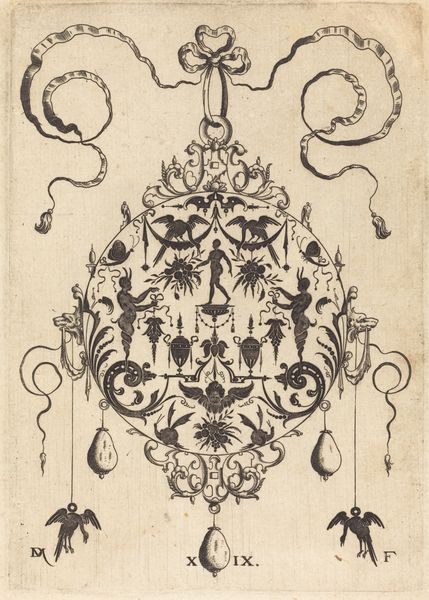

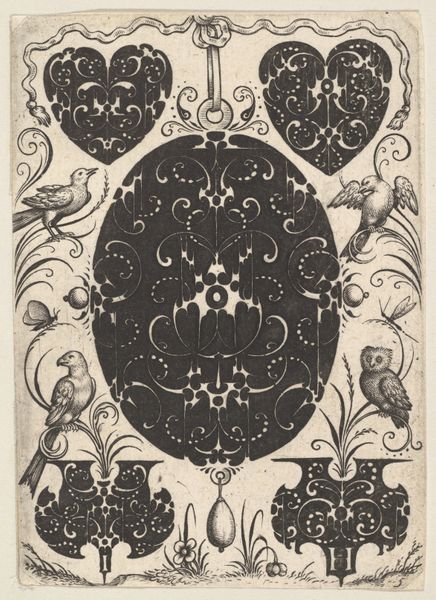

Editor: This intricate etching, "Title-Page: Brooch, Snail-like Animals Above, Centaurs with Banners at Bottom," created by Daniel Mignot in 1596, presents a rather fantastical design. The overall composition feels almost like a coat-of-arms, but with bizarre creatures. What is your interpretation of a work like this, one that blends decorative art with such strange figuration? Curator: Well, from a historical perspective, prints like this showcase the rise of ornament culture in the late 16th century. We see the influence of Mannerism, which valued artifice, elegance, and often embraced the bizarre. This print isn’t necessarily meant to convey a deep symbolic message but rather to serve as a model. How do you imagine these designs being used by contemporary artists and craftsmen? Editor: Possibly as inspiration for jewelry, or maybe embroidery patterns? The detail is incredible. Did Mignot create these images with a specific audience or purpose in mind? Curator: Precisely! These prints were pattern books, aimed at goldsmiths, jewelers, and other artisans. Mignot was actively shaping contemporary tastes and impacting the decorative arts industry. The inclusion of these strange figures adds to the overall sense of luxury and exclusivity of its patrons. It moves from being functional, becoming aesthetic and high art. Does knowing this shift your perception of the work? Editor: Definitely. Knowing that it served a practical purpose while also embodying the aesthetic sensibilities of the time gives it greater depth. I had assumed it was purely ornamental. Curator: The lines between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art were far more blurred then than we often assume today, remember this served not as high art, but informed high art, architecture, and aristocratic patrons, expanding the way visual language permeated culture at the time. I hope we consider these shifts when we examine the visual history, design, and artwork we view every day. Editor: This conversation has been enlightening; thank you. It helps me see these pieces in a more rounded way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.