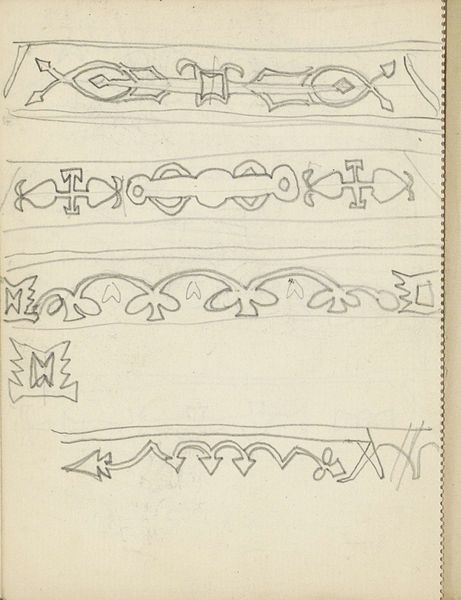

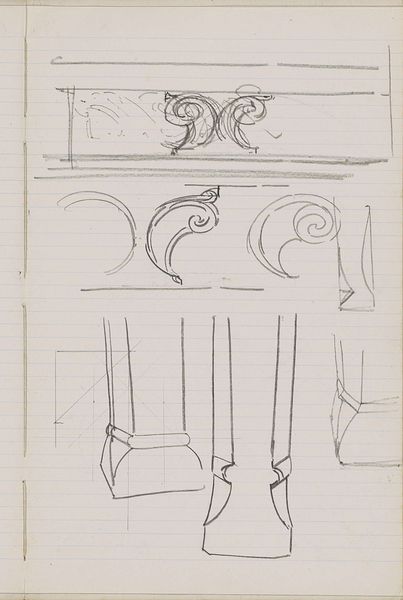

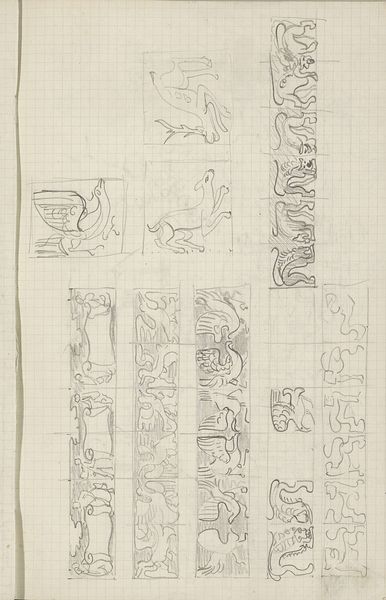

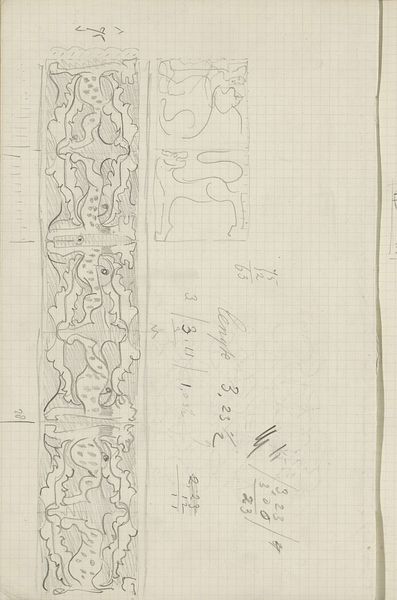

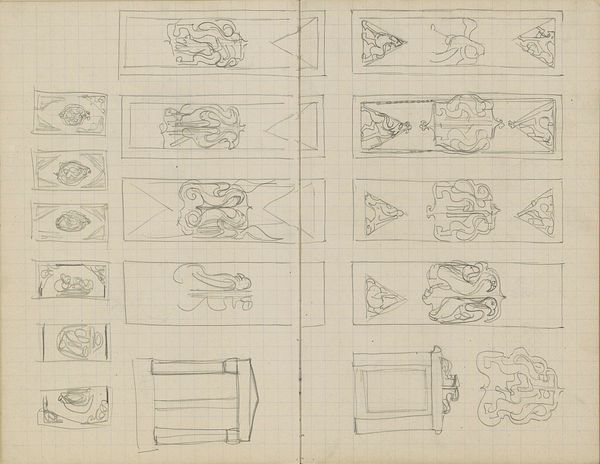

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

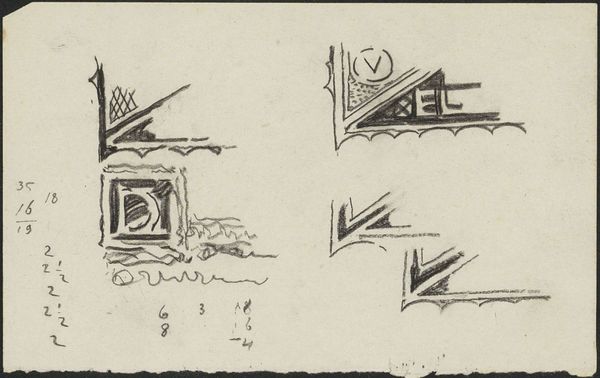

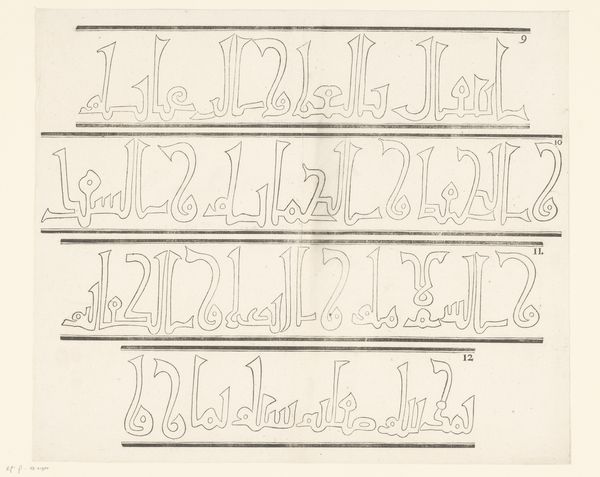

hand-lettering

#

hand drawn type

#

hand lettering

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

geometric

#

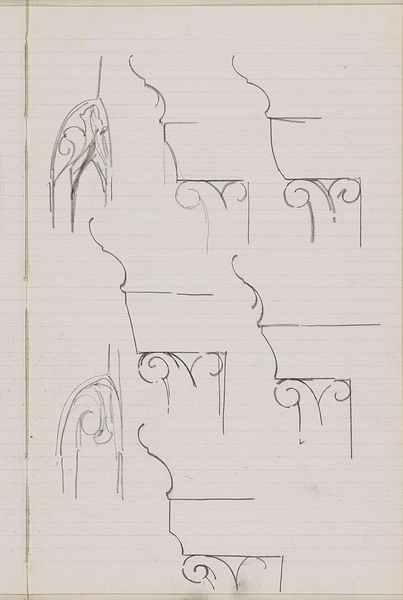

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

small lettering

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

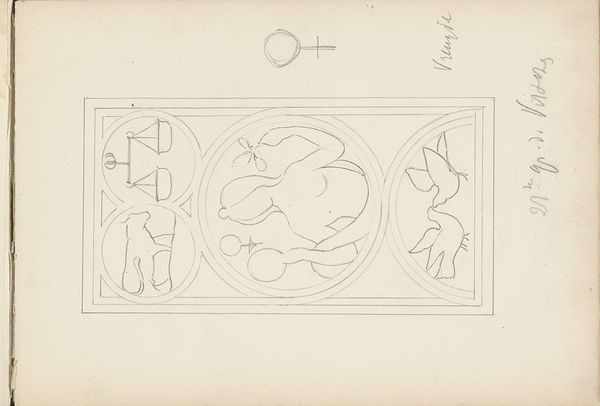

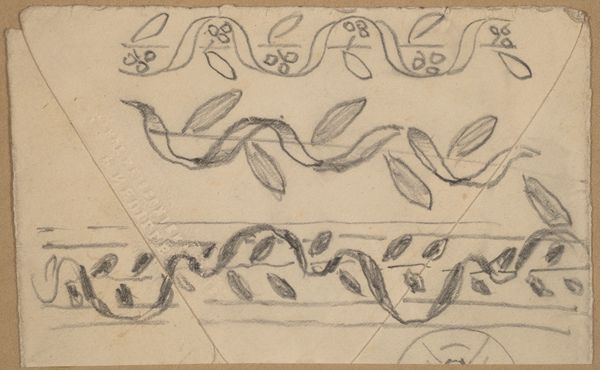

Editor: This is "Ornamenten met serpenten, kelken en bladeren," a drawing by Carel Adolph Lion Cachet from around 1928. It's a sketch on paper, featuring serpent and leaf motifs. I find the composition quite intriguing with its combination of geometric and organic shapes. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Beyond the surface appeal of geometric versus organic, I see a fascinating negotiation of power and identity. Consider the serpent, often a symbol of chaos, transformation, but also of colonized cultures, intertwined with goblets and leaves which reference growth and perhaps, domination through natural resources. How do these symbols work within the context of 1920s colonialism and burgeoning artistic movements in the Dutch colonies? Editor: So you're suggesting these aren't just decorative ornaments, but reflections of the social and political climate? Curator: Exactly! Cachet, who worked extensively in the Dutch East Indies, was undeniably influenced by his environment. We must critically examine whose perspectives are centered, and whose are marginalized through these visual choices. The very act of sketching these "ornaments" is one of appropriation of colonized forms for a Western context, isn't it? Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't considered. It makes you think about the power dynamics embedded even in seemingly simple design elements. Curator: Right! And the leaves, they're not simply decorative either. How are they presented? Are they vibrant or dying? Remember, botanical illustration often played a key role in resource extraction during the colonial era. Are these leaves celebrating nature, or cataloging it for exploitation? It forces us to consider the complicity of art in broader systemic oppressions. Editor: This has completely changed how I see this drawing. I now appreciate the depth and complexity of the cultural references. Curator: It’s a starting point. We should challenge every element and unravel these symbols to really decolonize our interpretation of this drawing. It encourages a more intersectional approach to art history, linking visual culture with socioeconomic realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.