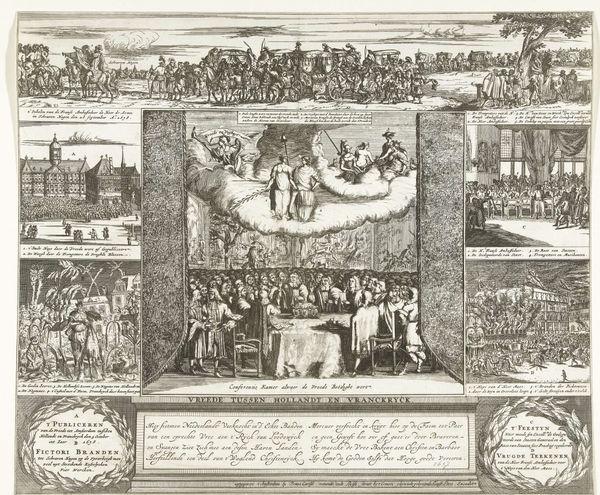

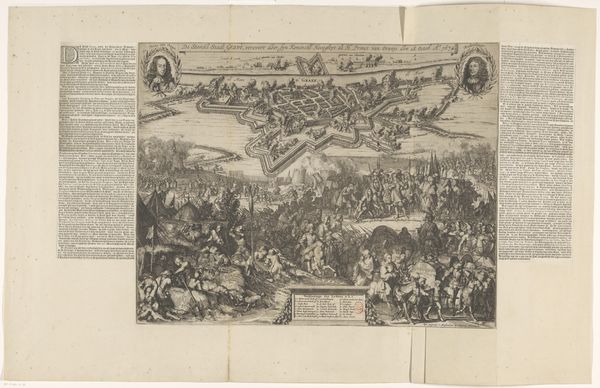

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 378 mm, width 497 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a fascinating print titled "Gebeurtenissen van 1672 tot aan de vrede met Engeland in 1674," or "Events from 1672 up to the Peace with England in 1674," made in 1674. It's currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. The artist is Romeyn de Hooghe, and the medium is engraving. Editor: It's overwhelmingly busy, isn't it? A real tapestry of violence, politics, and maybe even… resignation? The monochromatic scheme just adds to the somber feeling. Curator: It's incredibly dense, yes. De Hooghe was a master of allegory and symbolism, and this print encapsulates a tumultuous period in Dutch history. Each vignette represents a specific event, contributing to an overarching narrative of conflict and resolution. The central scene is a formal gathering, possibly a treaty signing, right? But surrounding it are these scenes of war and siege, almost like framing the central political act with its violent consequences. Editor: I'm drawn to the sheer amount of labor embedded in this piece. Think of the manual skill involved in creating such detailed lines on the plate. This isn't just "art"; it’s skilled work, an artifact of early printmaking techniques. It begs the question: Who was this produced for, and what purpose did these scenes serve at the time? Curator: That’s an excellent question. Engravings like these were often disseminated widely to inform the public about current events, to sway public opinion, or to immortalize historical moments through visual narratives. Looking at the details like the fortified cities, they were trying to evoke both the real space of that place and also instill a sense of pride for defense and strength of these settlements. It presents a shared visual language of history for the community, reinforcing cultural identity. Editor: So the material reality of the print —its replicability, the relative accessibility of this format compared to, say, an oil painting— allowed it to become a powerful tool for the dissemination of ideology. These scenes weren’t just neutral documentation; they actively shaped public understanding. I wonder how the artist made choices on what to depict, who commissioned it and for what particular intention. Curator: Absolutely. These choices, these constructed images shaped the national memory and public consciousness during a period of intense conflict. And now, centuries later, this work carries symbolic weight to inform and educate the audience with the context of Baroque, cityscape and war. Editor: Thinking about the original act of creation in such painstaking detail gives one respect for the dedication. Curator: Indeed. It makes you reflect on not just the artistry, but also the history and meaning that visuals pass on through time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.