print, engraving

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

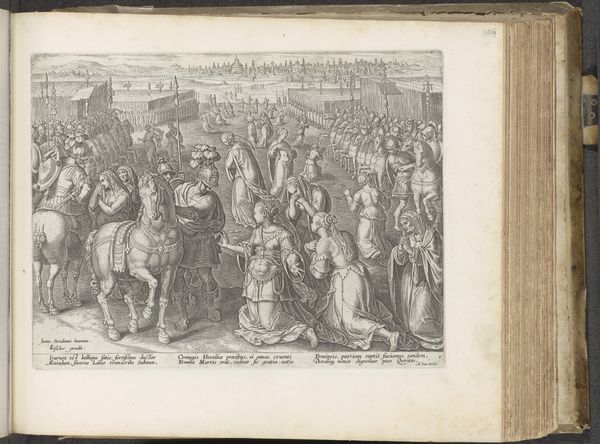

Dimensions: height 217 mm, width 302 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This engraving, "Aziatische straffen" or "Asian Punishments," made sometime between 1682 and 1733 by Romeyn de Hooghe, presents a really detailed and somewhat unsettling scene. It feels incredibly dense with figures and actions. How would you interpret what’s going on here, especially in relation to the period in which it was made? Curator: What we’re seeing is deeply embedded in the socio-political context of the Dutch Golden Age and its burgeoning global trade and colonial ambitions. This print offers a visual representation – or perhaps a projection – of power dynamics. Notice how de Hooghe constructs a scene ostensibly about “Asian Punishments.” What’s immediately apparent is the staged spectacle of it all, don't you think? Editor: Yes, the 'staging' does stand out. All those people watching... Is de Hooghe suggesting something about the act of witnessing or even the justification of colonial practices through this portrayal? Curator: Precisely. Prints like these were circulated widely. They served not only as records but as tools for shaping public opinion, feeding into existing European perceptions, and perhaps even solidifying justifications for intervention in “foreign” affairs. The “punishments,” rendered in such detail, cater to a European fascination with the ‘exotic’ and reinforce a sense of cultural superiority. How does the implied narrative within the composition impact our viewing experience, considering its political weight? Editor: It definitely makes you think about the role of the artist, not just as an observer but as a participant in shaping cultural narratives. Curator: Exactly. By depicting these scenes of ‘justice’ being served, de Hooghe reinforces particular viewpoints and affects how the Dutch public viewed their colonial endeavors. We begin to question the agency and ethics behind the visual portrayal itself. I think recognizing this power dynamic allows us to understand not just the image, but its effect on contemporary audiences. Editor: I never would have looked that deeply into just an image on old paper, but thanks to your explanation, it tells us so much about the context of its creation. Curator: And hopefully inspires us to think more critically about imagery today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.