Dimensions: height 28.5 cm, width 23.2 cm, depth 3.8 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

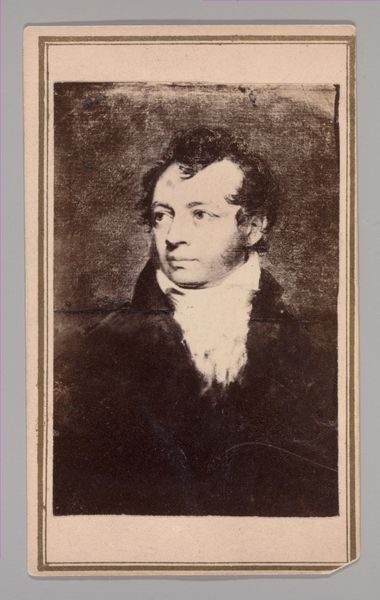

Curator: Before us hangs "Jacob Jurriaan de Friderici," an oil on canvas portrait completed before 1860 by Nicolaas Pieneman. The work is currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial impression is a study in controlled power. There's a somber intensity to his gaze, which dominates despite the darker hues. It suggests a personality deeply entrenched within societal structures. Curator: Indeed, Pieneman, who worked in the Romantic style, frequently focused on historical depictions and portraits of prominent figures. This work, representative of academic art, captures more than mere physical resemblance. Consider the implicit narratives woven into the piece, with symbolic weight subtly implied. Editor: The man's assuredness is visually constructed; I'd guess it speaks to the specific societal role assigned to men during this historical moment. His attire— the high collar and dark overcoat—seems less a matter of personal taste and more a signifier of societal rank and power. Curator: That black coat absorbs a lot of the light in the painting, yet his face is brightly illuminated. We focus our immediate attention on the sitter’s personality, despite his garb conforming to established expectation. Even his hair seems consciously arranged. Editor: Precisely. We should also think about the cultural framework and societal privileges granted to the sitter as a white man, no doubt a member of the wealthy Dutch upper class, which undeniably shapes the representation itself. Even now, that constructed history informs our perception. Curator: I’d say it's not just a social construction but an intentional assertion of identity through visual language, one layered in implicit narratives and familiar tropes that an audience of that time would quickly understand. Consider that for generations images played the important role of defining social standing. Editor: And images like these still wield influence, albeit perhaps in subliminal ways. Deconstructing them exposes the ways such compositions might re-inscribe old hierarchies of wealth and influence and invite critique and re-evaluation of societal norms. Curator: That opens fascinating questions about the role of museums, which often hold power to both display and interpret the very codes these portraits present. Editor: Well, precisely. By critically analyzing such artworks, perhaps we find ways to dismantle such antiquated frameworks while expanding modern audiences’ appreciation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.