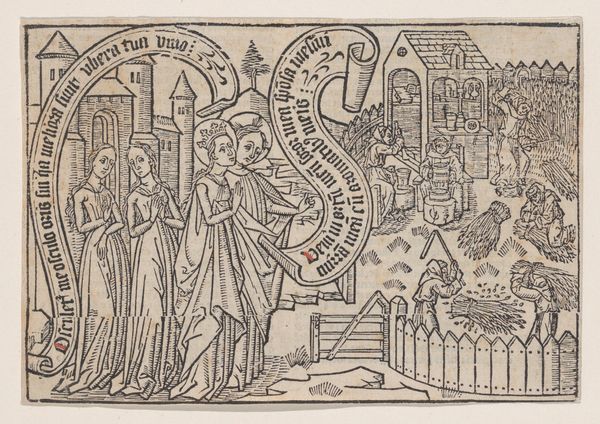

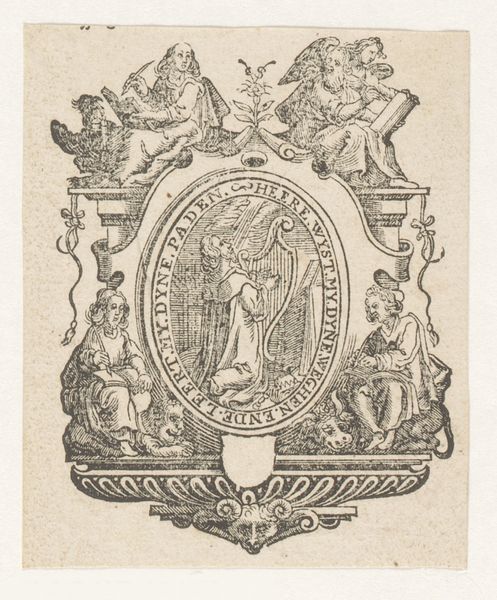

Come My Beloved, Let Us Go Forth Into the Field, illustration from a Canticum Canticorum blockbook, 2nd edition 1460 - 1470

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, woodcut

#

drawing

#

medieval

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

Dimensions: Sheet: 5 1/4 × 7 7/16 in. (13.3 × 18.9 cm) Block: 4 7/8 × 7 1/4 in. (12.4 × 18.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What an intriguing print. This woodcut, titled "Come My Beloved, Let Us Go Forth Into the Field," is an illustration from a Canticum Canticorum blockbook dating back to the period 1460 to 1470. It’s currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first impression is one of delicacy despite the bold lines typical of woodcut. There’s a remarkable balance between the figurative elements and the text. The linear perspective and composition contribute to a rather harmonious, dreamlike quality. Curator: Absolutely. These blockbooks were crucial in disseminating religious texts and imagery to a wider audience during the late medieval period. The figures represent, it's thought, the Bride and Bridegroom from the Song of Songs, part of the Old Testament canon depicting themes of divine love and yearning between God and Israel, later reinterpreted as Christ and the Church. Editor: Note how the artist uses line to delineate space and form, from the draping of the robes to the rendering of the landscape. See how the framing banner with its text integrates so well with the narrative scene, enclosing and adding visual interest while supporting the overall symbolism. It all forms a closed and balanced design, in line with medieval tastes. Curator: It’s important to remember that while blockbooks made information more accessible, access was still deeply mediated by religious and social norms. Each scene would have reinforced theological interpretations and specific devotional practices among the audiences encountering it. These served as both an educational and deeply ideological tool. Editor: Thinking purely in terms of form, that banderole lends the print a rhythm, wouldn’t you say? The placement of figures to architecture creates an aesthetic tension between foreground and background, with both serving narrative and decorative roles. I love the stylized roses framing the Angel, an element echoing love and divine grace, and how the negative space creates texture within these shapes, drawing the viewer's eyes from figure to figure around the frame. Curator: I agree. Considering the socio-cultural context, one might consider this a snapshot of the visual culture circulating within a particular religious milieu. The level of detail reveals what artisans thought audiences would have desired or responded to—an angle to the historical relevance often overlooked today when one considers the social power relations in such circumstances. Editor: In a sense, each viewer's eye deciphers a coded visual structure embedded within those very aesthetic properties; whether through form or through meaning the woodcut still speaks, I’d say, today. Curator: Well articulated! Editor: Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.