engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

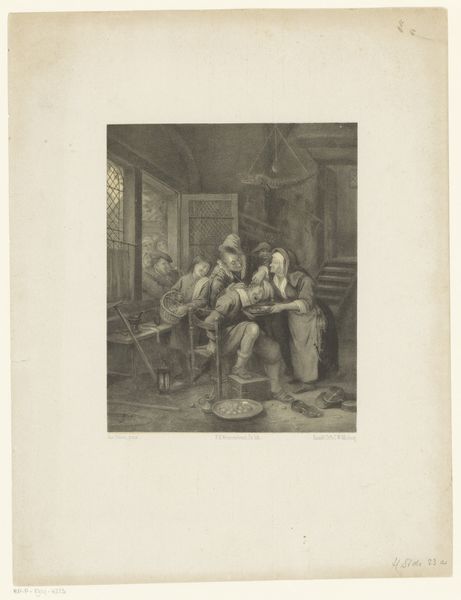

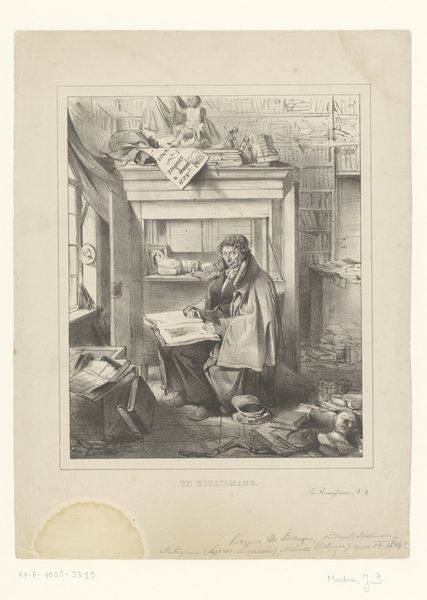

Dimensions: height 356 mm, width 263 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, this is certainly... something. Editor: Indeed. May I introduce "Man behandelt patiënt met beenwond," an engraving by Isaac Beckett from around 1681 to 1688? It depicts a man treating a patient's leg wound. The overall impression is surprisingly intimate, but undeniably gruesome, no? Curator: Intimate, sure, in the same way observing any kind of work is. For me, it is interesting to observe what tools are employed in this scenario. The room around them seems crammed with alchemical paraphernalia, vials, and instruments suggesting the broader context of early medical practice. You see the material basis of care in play here. Editor: I agree the staging tells a rich story. The Baroque period’s fascination with the body, especially bodies marked by illness or injury, and how it played out through print culture for wider audiences. It is interesting how Beckett chose to disseminate medical procedures, essentially turning them into public spectacles. Curator: Exactly! And Beckett's expertise with engraving plays a crucial role. The intricate detailing that reveals textures and gradations of light and shadow. Think about it: what paper was used, how widespread would prints like these be, how affordable? These tangible details ground our understanding of it all. Editor: Certainly. I’m also drawn to the setting—the seemingly mundane interior infused with a palpable sense of human drama. And isn’t that fascinating? It’s a glimpse into medical treatments within society at the time, making you wonder about hygiene and broader perceptions of healthcare during the Dutch Golden Age. Curator: I also note what appears to be a rudimentary prosthetic hanging from the ceiling, quite a symbolic comment. And by observing all this it moves beyond mere “genre painting” or a depiction of medical history, to the socio-economic infrastructure supporting care for the unwell and injured. The engraving serves as evidence of the materiality of historical processes and procedures. Editor: Right. Beckett seems to have understood the inherent theatricality of medical encounters. But by presenting this in print, how does he aim to affect us? Are we supposed to be learning from the engraver's precise recording? It asks deeper questions. Curator: A vital reminder that even within these seemingly simple prints, so much can be illuminated once we turn towards a study of what constitutes its making and the forces of its production. Editor: Indeed. By contextualizing these prints, we gain an understanding not just of past artistic styles but also the intricate societal tapestry from which it all arose.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.