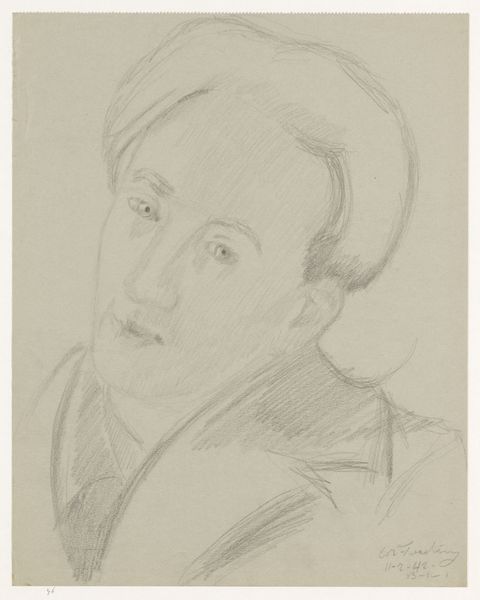

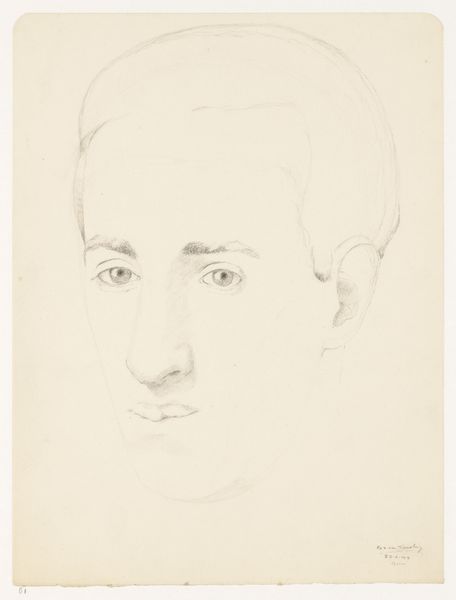

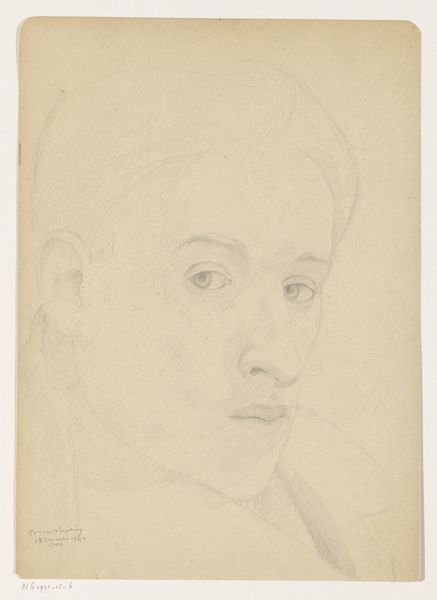

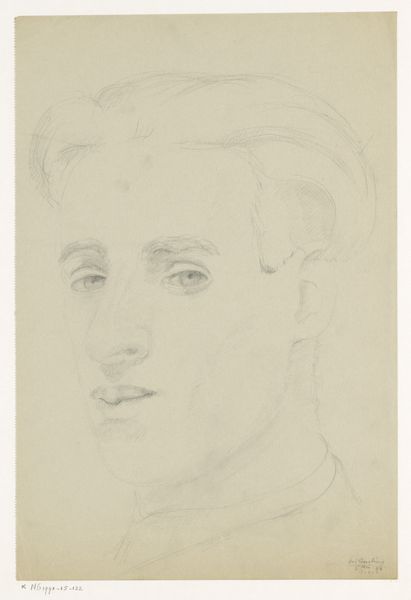

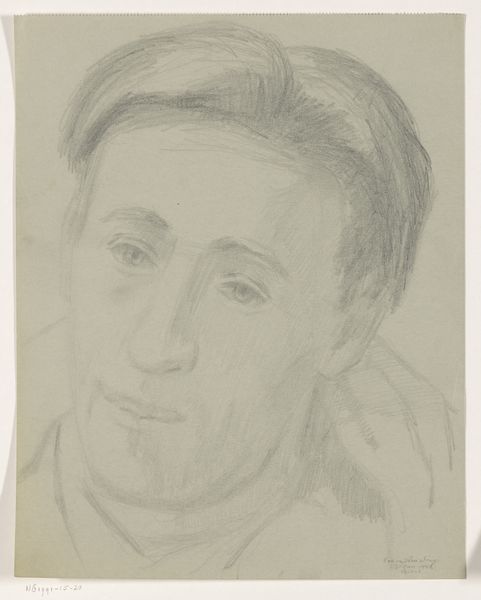

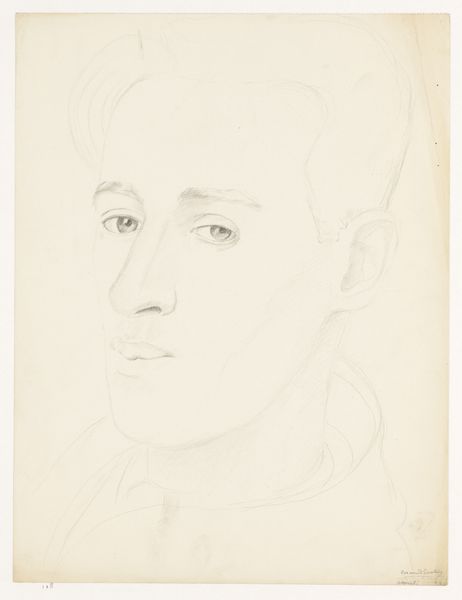

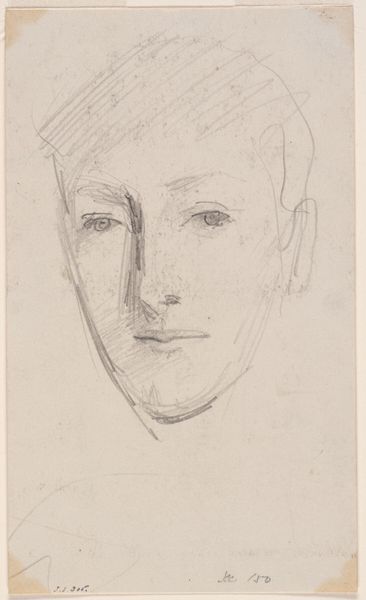

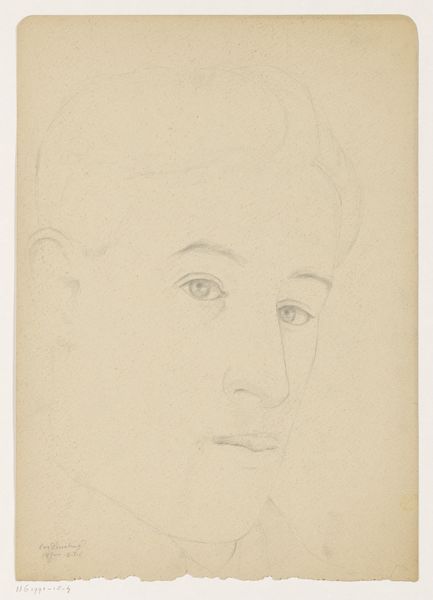

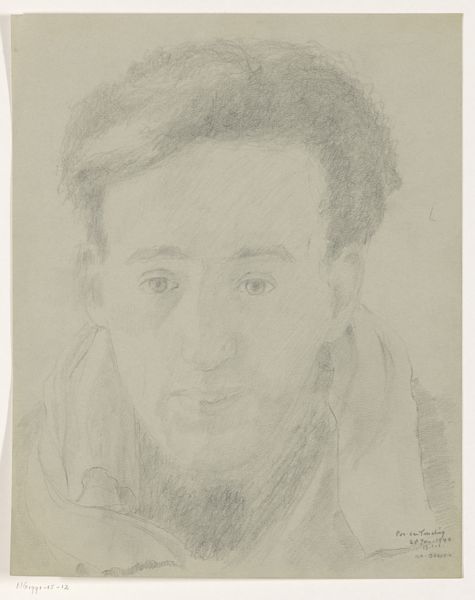

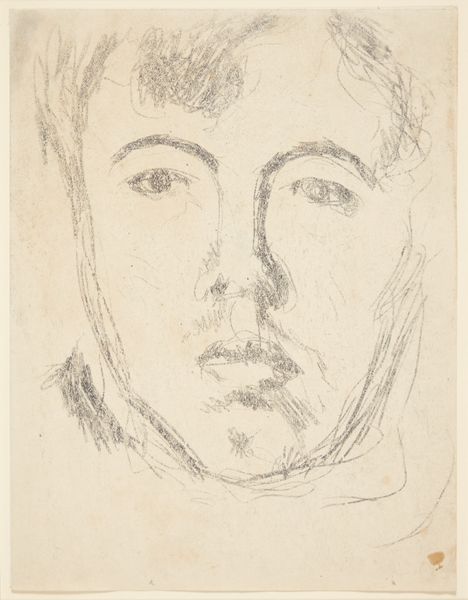

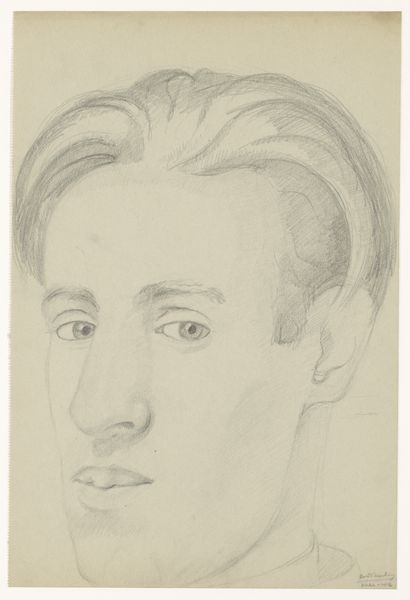

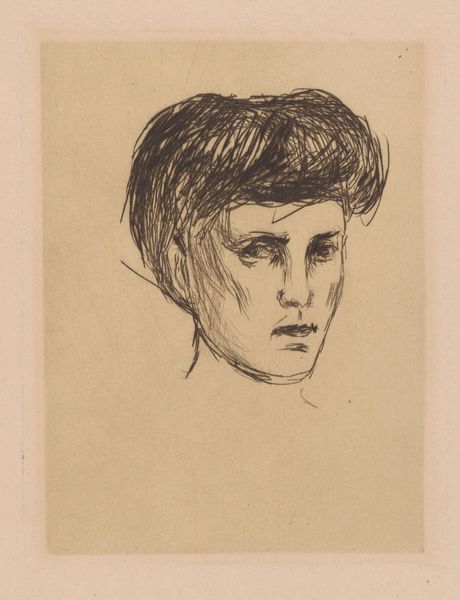

Dimensions: 304 × 236 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Charles Maurin's "Portrait Head of a Young Woman," created around 1900. It's a print, likely made with graphite, chalk, and pencil on paper. Editor: It has an intimate, almost fragile quality. The lines are so delicate, the subject feels very immediate and present. It makes me think of lost dreams and whispered secrets. Curator: It’s interesting that you say that, considering Maurin’s work was often intertwined with socialist and anarchist circles in Montmartre at that time. This wasn’t just about aesthetic representation, but reflecting social realities and perhaps offering subtle commentary through the portraits. Editor: Ah, situating her in that context certainly shifts my perspective. Was she someone of particular significance within those movements? Is this quiet strength a deliberate visual choice meant to align with the era's New Woman archetype and their increasing role in politics and society? Curator: It's difficult to ascertain her precise role but what is evident in much of Maurin’s portraiture is his handling of line and texture; he wasn't just interested in likeness. It’s about the act of drawing itself, the labor involved, the choice of humble materials...all speaks to challenging academic art standards, much like those political circles sought to upturn social hierarchies. Editor: Absolutely. The deliberate rawness rejects artifice. You can almost feel the artist's hand moving across the page, suggesting both vulnerability and intentionality. Were such drawings considered preliminary studies or finished works meant for broader consumption in print? Curator: Likely both, I would argue. Reproducing artworks allowed for broader distribution and a potential for accessibility, thus democratization, aligning with some socialist principles that favored art serving wider audiences rather than wealthy elites alone. Editor: That definitely provides food for thought. So, this quiet portrait potentially reflects a dialogue about female agency, social change and even accessible production of artworks, rather than solely concerning aesthetic grace. Curator: Precisely. Materiality speaks volumes here about choices tied to production and access, echoing the artistic and political climates converging in that era. Editor: I will never see a simple portrait the same way again, now. Curator: Which perhaps confirms its lingering power and potential for layered readings.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.