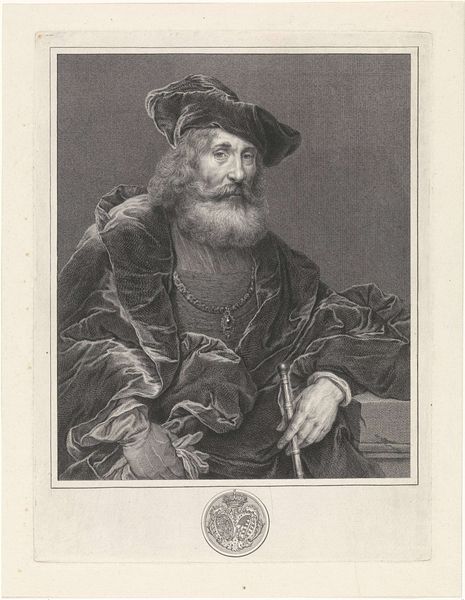

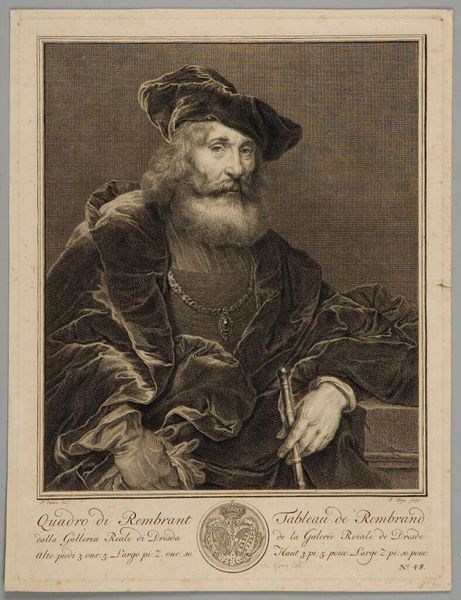

En gammel invalid. Portræt af en soldat 1837 - 1838

0:00

0:00

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

realism

Dimensions: 62 cm (height) x 58 cm (width) (Netto)

Curator: Emil Bærentzen created this poignant portrait, "An Old Invalid. Portrait of a Soldier," sometime between 1837 and 1838. It's currently held at the SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark. What's your immediate reaction to it? Editor: It strikes me as profoundly sad. The dim lighting, the way the subject's eyes seem clouded with memory…it's not just a portrait, it feels like an indictment of war, of systems that discard individuals. Curator: Yes, the figure carries an almost archetypal weight. Soldiers, historically, are symbolic of both heroism and sacrifice, aren’t they? And in many cultures, elder figures, such as this soldier, can symbolize a past era. Look at his weathered face, his drooping hat. It speaks volumes. Editor: Precisely. This isn't a glorification. Bærentzen uses realism, almost brutal realism, to show the cost. This man is no longer useful to the military-industrial complex. What happened to his body? What sort of societal support was in place to aid someone damaged so severely? How does nationalism treat someone used up and forgotten? Curator: Well, considering its era, the painting might hint at broader cultural shifts toward greater awareness of social inequalities. Romanticism was prominent then and combined well with realistic representation here, offering empathy for the marginalized. Editor: Absolutely. By painting him in oil, with that almost reverent attention, Bærentzen gives the invalid a presence, a visibility denied to him in broader society. Look at the red lapels. Red signals anger or aggression; perhaps this is Bærentzen, or even the subject, showing rage. It also makes me think about how his red lapels stand in stark contrast to the dark, somber setting of the painting. Curator: His red lapels almost act as a marker of former rank, highlighting a present demotion to overlooked civilian. A reminder that the red of military pride fades into the shadows. Editor: In that regard, then, it challenges any idealized version of patriotism. It's a commentary on the state, the nation, maybe even militarization. There’s an undeniable contemporary resonance, too. Curator: It is a disquieting piece, then, urging a critical evaluation of heroes and victims, memory and forgetting. Editor: It definitely makes me question the narratives we uphold as a society. It encourages us to see the human cost of ideological wars or even personal conflict in a broader picture. It challenges us to see our own complicity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.