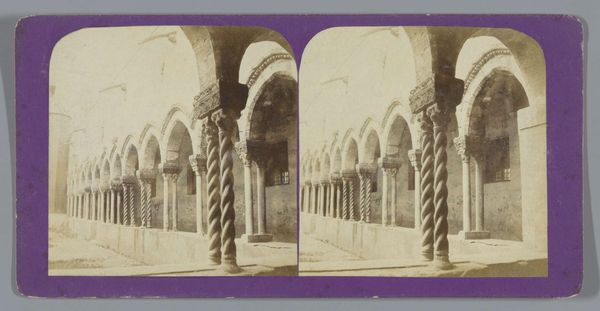

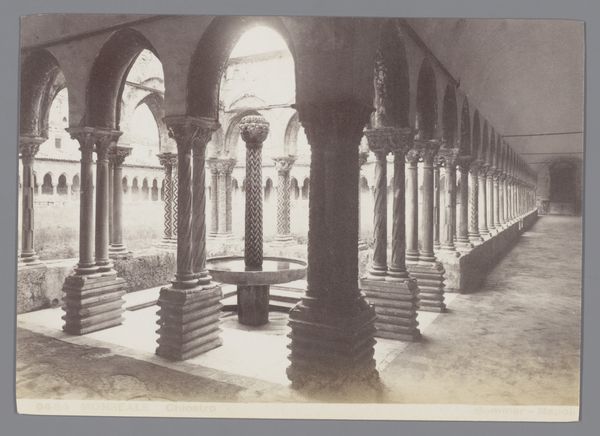

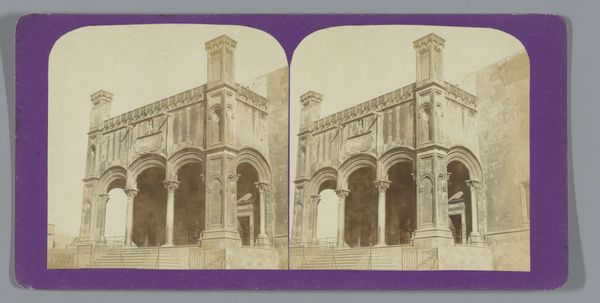

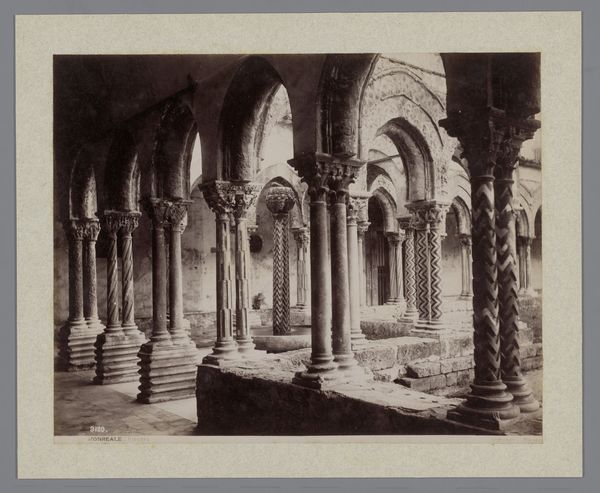

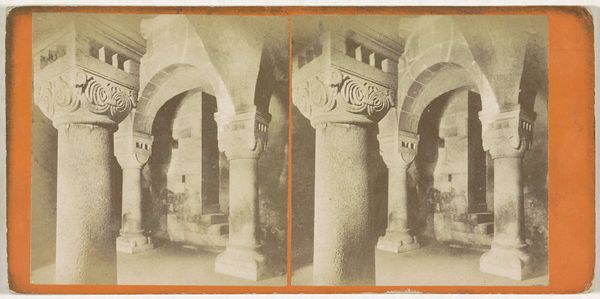

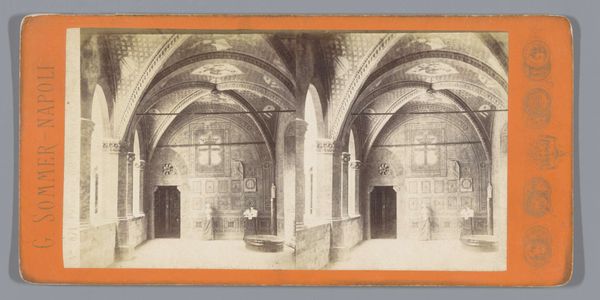

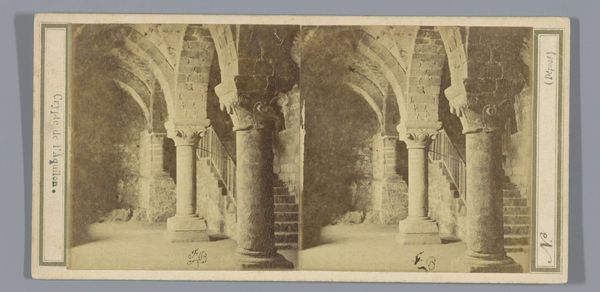

Gezicht op de kloostergang aan de binnenplaats van het klooster van Monreale 1862 - 1876

0:00

0:00

print, photography, architecture

#

medieval

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

geometric

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

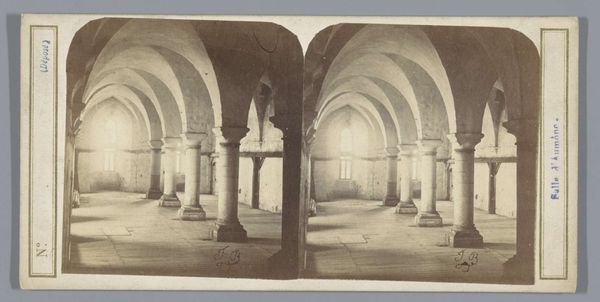

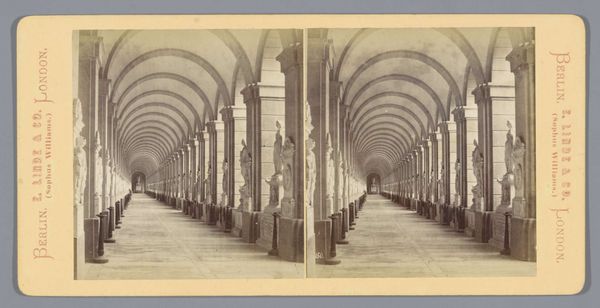

Curator: This is a stereograph by Jean Andrieu, taken sometime between 1862 and 1876, titled "View of the cloister in the courtyard of the monastery of Monreale." It's a photographic print meant to be viewed with a stereoscope. Editor: Wow, it’s incredibly serene. The repetitive arches create this rhythmic, almost hypnotic effect. The texture in the pillars adds depth, but the tone evokes a very quiet stillness. Curator: Absolutely. Stereographs were mass-produced, a popular form of entertainment and documentation in the late 19th century. Think of them as the VR of their day. This one showcases the architectural details of Monreale's cloister, likely intended for a middle-class audience interested in travel and culture but unable to make the trip themselves. The process speaks to how photographic reproduction made experiencing art and architecture more widely accessible. Editor: That accessibility is key. Considering the history of the Sicilian Norman kingdom and its complex interactions between Christian, Islamic, and Byzantine cultures, a place like Monreale held deep symbolic meaning. This image, circulated broadly, participated in constructing ideas about Sicilian identity, European history, and perhaps even Orientalism. Curator: Interesting. From a material standpoint, consider the labor involved: the photographer, the printing technicians, the distribution networks. Stereographs became affordable due to mass production and division of labor; their widespread availability drastically changed how people experienced art. Editor: And that accessibility has its shadows. Who gets to control the narrative presented in these widely disseminated images? How does a simplified visual experience shape public understanding, especially regarding regions and cultures with complicated colonial pasts? It reminds us that documentation is never neutral. Curator: Very true. The photograph, despite its seeming objectivity, is a carefully crafted product reflecting the photographer’s choices and the market’s demands. The stereograph miniaturizes grand architectural spaces, making culture easily consumable. Editor: Looking through the lens of history and social context reveals that what seems like a simple image can prompt a range of discussions regarding accessibility, labor, and cultural representations. It calls upon us to constantly critique and examine the production, consumption, and distribution of images, especially those tied to cultural heritage. Curator: Precisely, by considering these mass-produced images, we gain an entry point into how materials and distribution contribute to meaning and reshape cultural perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.