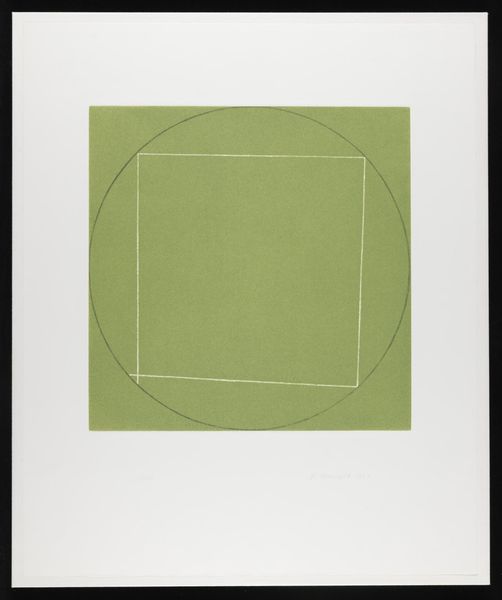

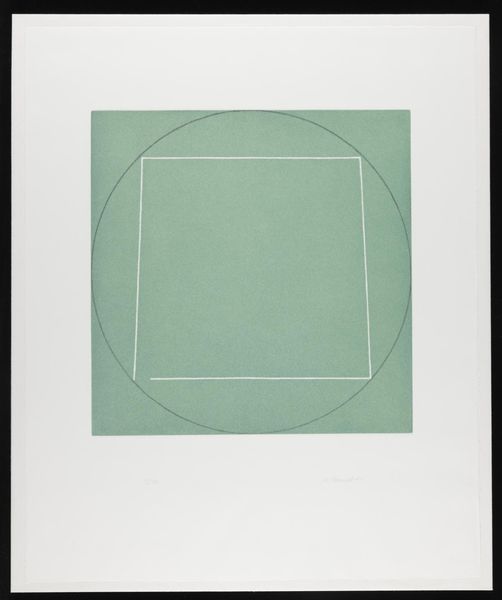

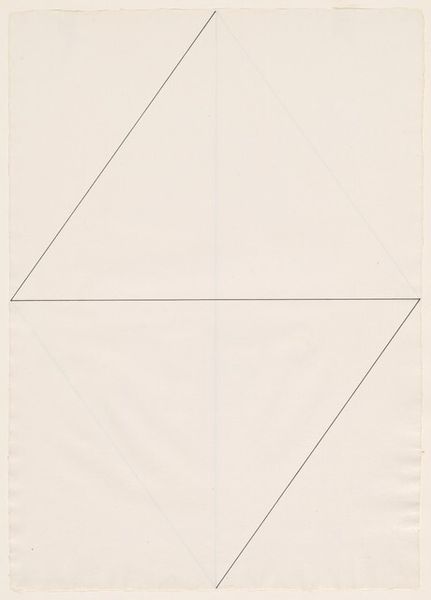

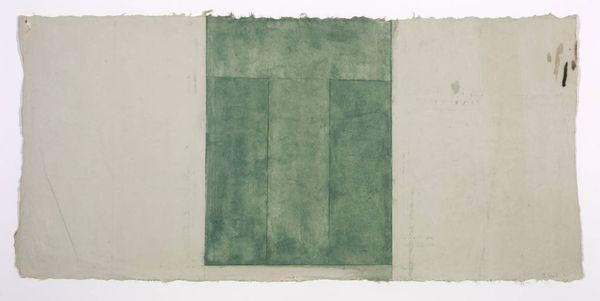

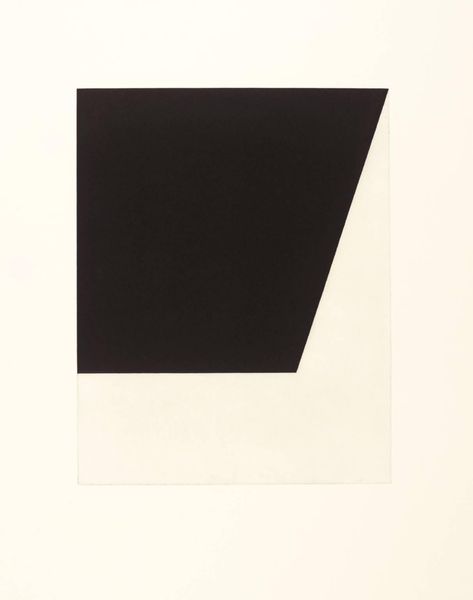

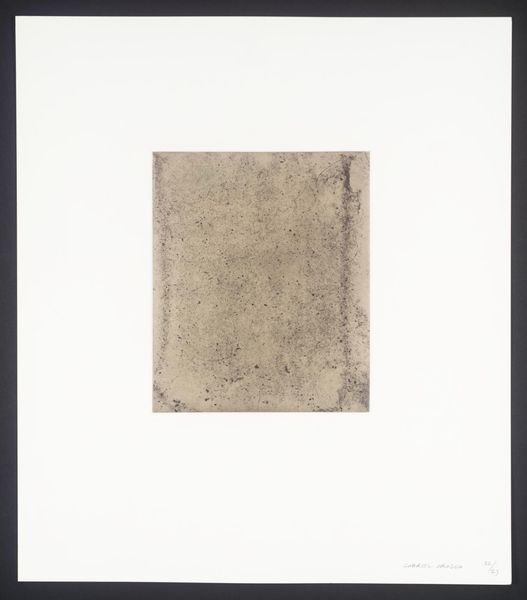

Untitled from Seven Aquatints 1973

0:00

0:00

robertmangold

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US

Dimensions: 40 x 40 cm

Copyright: Robert Mangold,Fair Use

Curator: Standing before us is an aquatint by Robert Mangold, created in 1973. It is part of a series called "Seven Aquatints". Editor: The simplicity is striking. It’s mostly a soft, muted green square, and the lines create this understated tension—a circle just peeking out from the edges, suggesting more than we see, and a square nestled inside. It feels... reserved. Curator: Reserved is a great word. Mangold's process here, like much of his work, is deeply rooted in exploring the properties of his chosen medium. The aquatint method allows for these subtle gradations in tone and texture. Consider the flat planes of color— achieved through meticulous work on the copper plate and how that technique contributes to the minimalist aesthetic. How do you think its simplicity fits in the broader context of the MoMA collection? Editor: Well, it's impossible to divorce this piece from its historical moment, emerging from the minimalist and Color Field movements. It speaks to that ethos of stripping away narrative and representational elements to reveal the fundamental properties of color and form. In terms of the institution, MoMA has a long history of championing these movements. Curator: Exactly, but I also think it's important to recognize the tension within that institutional embrace. Minimalist works were often received as austere and inaccessible by the broader public, and in fact were intended to create those tensions! There’s an element of challenge embedded in their seeming simplicity. Think about how the piece prompts questions about perception and meaning-making. How far can an artwork be reduced before it loses its ability to communicate? Editor: Yes, the perceived inaccessibility became part of its narrative! It makes me consider its placement within gallery spaces then and now. How does this quiet geometry function differently within a museum versus a more commercial gallery or even a private collection? Curator: These are great considerations that also invite audiences to rethink those hierarchical notions between the public, private, high, and low realms of artistic production and consumption. What kind of labor went into producing such minimalist work? I suspect that asking such a question can open discussions of class and the socioeconomic conditions in which these types of objects were circulating. Editor: A piece that is both visually calm but conceptually complex. Thanks for sharing that with me, and those final notes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.