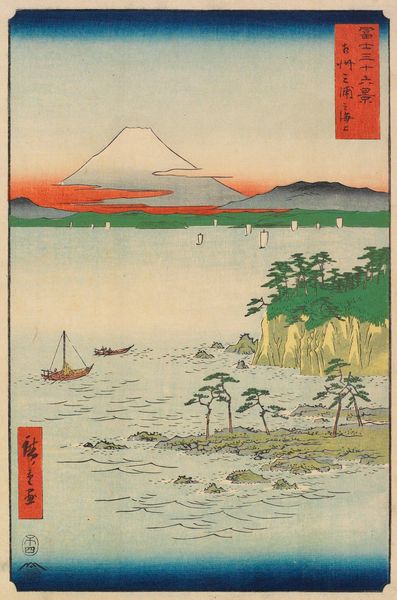

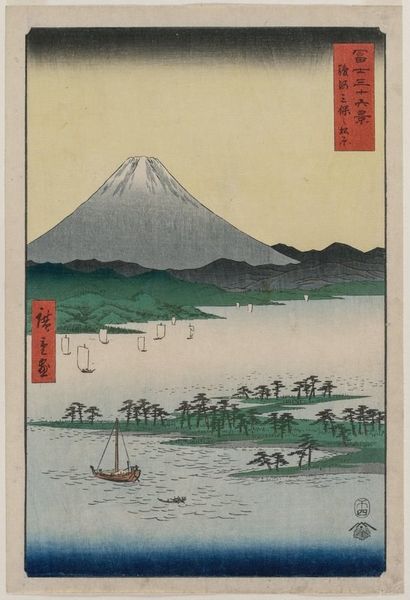

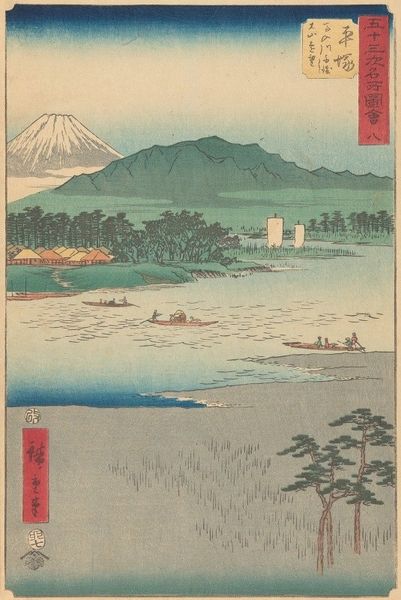

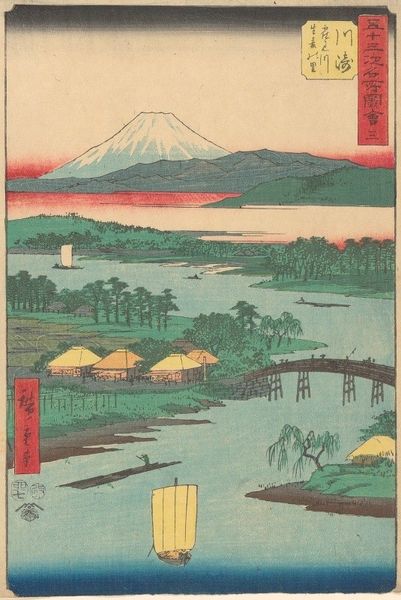

print, ink, woodblock-print

#

water colours

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

woodblock-print

#

orientalism

#

watercolor

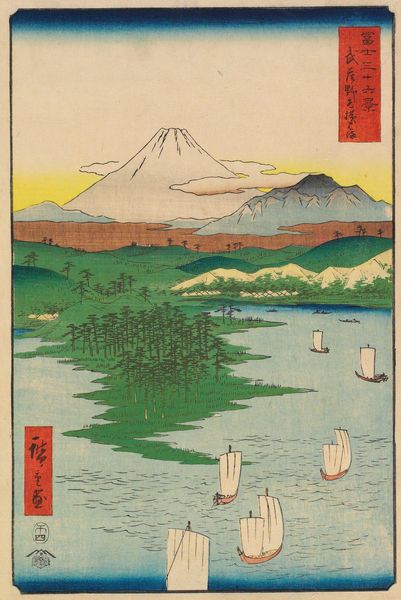

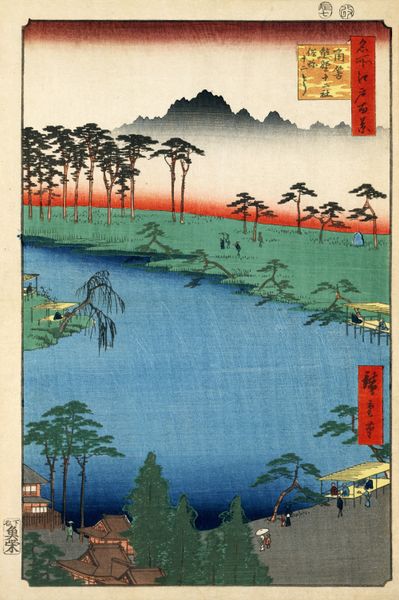

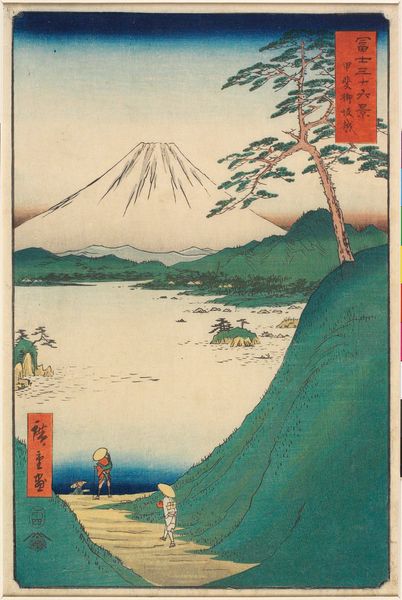

Dimensions: 13 1/4 × 8 11/16 in. (33.6 × 22 cm) (image, vertical ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: We're looking at "Jewel River in Musashi Province," a woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige, possibly from 1858. The color palette is gorgeous! It makes me feel a sense of tranquility. What's your perspective on this, looking at it with a materialist lens? Curator: Indeed. We must consider the specific materials and techniques of Utagawa Hiroshige. Woodblock printing itself is crucial, a process deeply embedded in craft and labor. Who harvested the wood? How were the pigments sourced and combined? What socio-economic factors determined the availability of such high-quality materials, affecting both the artistic and working classes in 19th-century Japan? This landscape is more than just aesthetics, isn't it? Editor: So, even this serene scene of nature becomes a study in production and class? I hadn’t considered the social implications behind creating the piece itself! How does that inform our reading of the landscape, beyond the beauty? Curator: Precisely. Think of the woodblock as a matrix. The matrix carries inherent information about material conditions of production that made the print possible. Look closer—do the printing methods, the layering of ink, reveal a connection between the print's form and its content? How does that reflect the relationship of human labor to nature that is visualized in this image? Does this suggest an idealized view of that relationship, perhaps concealing labor's more strenuous aspects? Editor: That is something I hadn't fully appreciated before! It's amazing how deconstructing the art's production allows for a more intricate perspective. Curator: Yes, viewing art from a materialist lens reminds us that aesthetics, craft, society, labor, and consumption are intrinsically interwoven. We're not just viewing a river, but a record of material relationships!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.