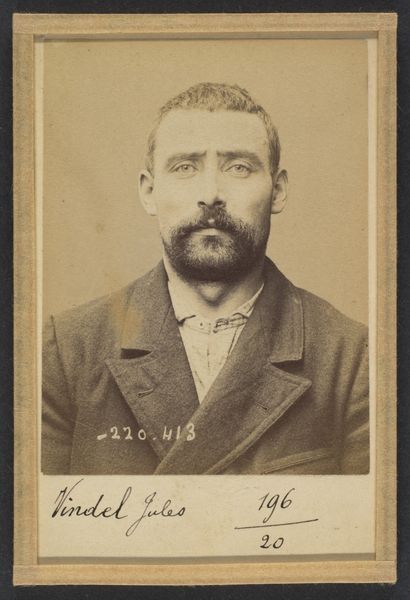

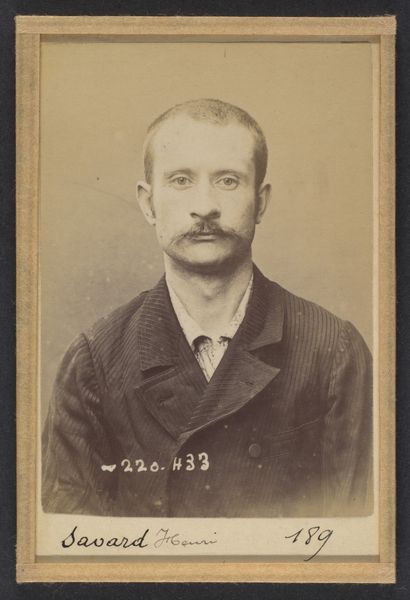

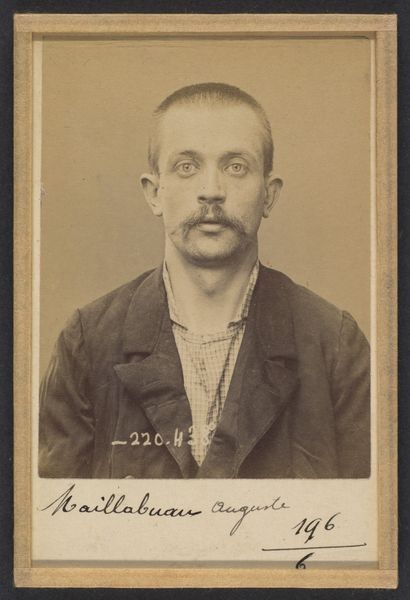

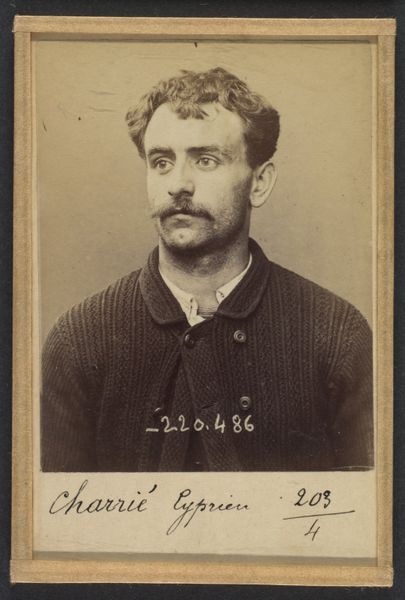

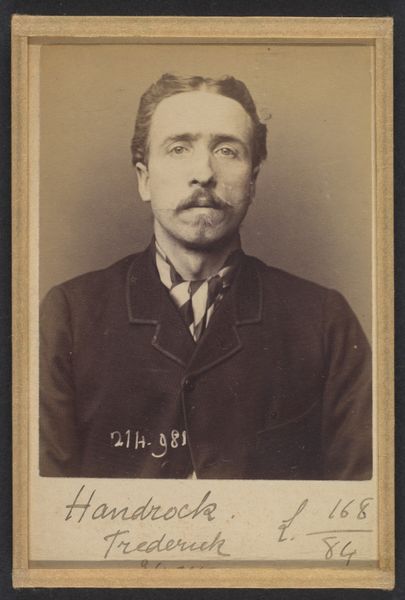

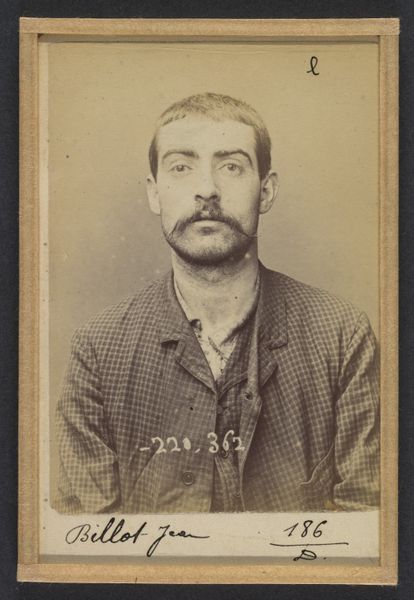

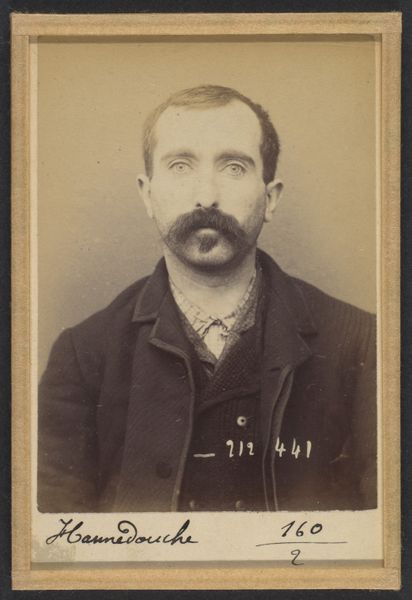

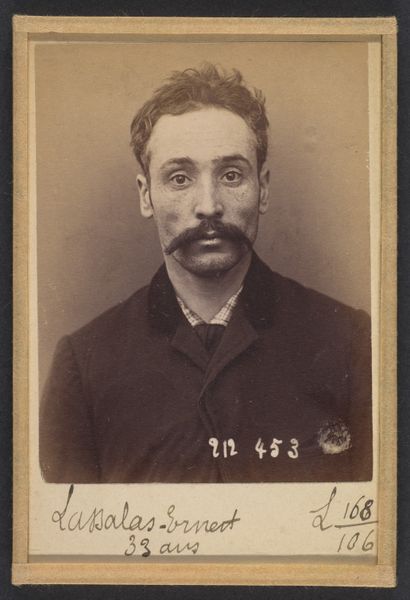

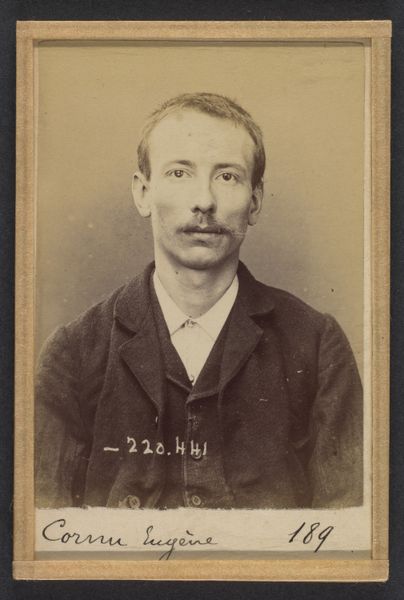

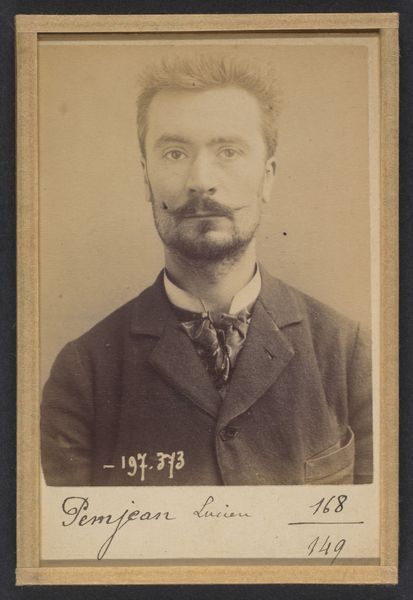

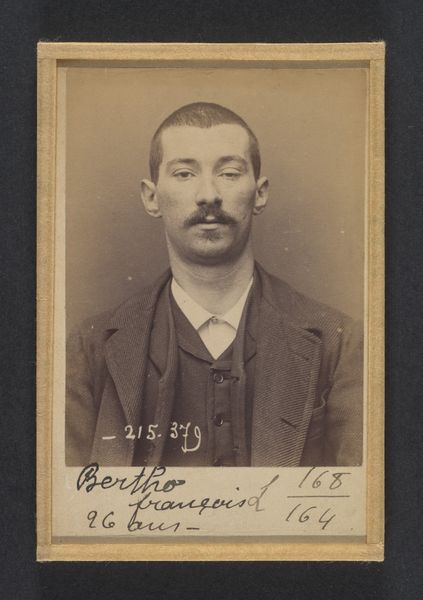

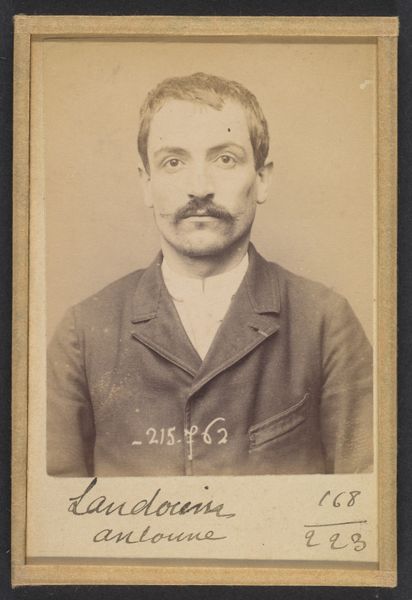

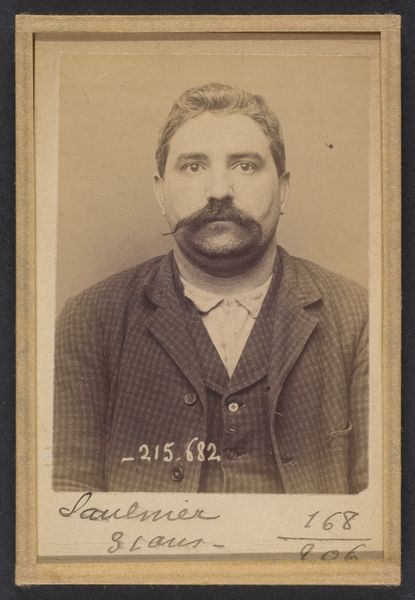

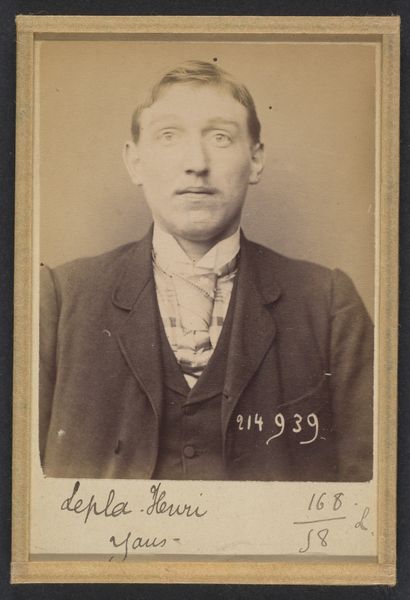

Villa. Jean. 29 ans, né à Farini d'Olma (Italie). Manoeuvre. Anarchiste. 2/3/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

photography

#

history-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Alphonse Bertillon’s, “Villa. Jean. 29 ans, né à Farini d'Olma (Italie). Manoeuvre. Anarchiste. 2/3/94.” dating from 1894. It's currently part of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It’s rather stark, isn’t it? A study in sepia tones. The composition is rigidly frontal, drawing all attention to the man’s expression. Curator: Precisely. Bertillon pioneered forensic photography and this piece serves as an excellent illustration of how photography, through precise structure and formal execution, could become a tool of the state. Note the way the inscribed text acts as objective data. Editor: Yet there's a clear tension here, because, as you note, while purporting to be objective, it inescapably betrays its subject. The clothing—the rough jacket, the worn shirt—all speak to a specific socioeconomic background. A kind of material poverty is on stark display, isn’t it? The means and method create this effect. Curator: Indeed. And further, by combining the written record with a reproducible photographic image, the medium itself allowed for easy dissemination and control, a novel function. One can appreciate how, through Realism, the art here reflects a social anxiety but also mirrors a positivist worldview. Editor: Yes, photography becomes complicit in the processes of categorization and othering, furthering this “us” vs “them” divide, a division rooted not in intrinsic difference but in the conditions of labor and capital at that specific point in the late nineteenth century. Even this apparent attempt to objectively document fails. The tones speak. The materials themselves have weight. Curator: This discussion really reveals a certain irony in how photography was perceived. What seemed an instrument of scientific accuracy inevitably carries profound sociological weight. It shows how much context influences observation, something art strives to transcend, yet remains rooted in. Editor: A point well made. The very materiality of art production—the photographic chemicals, paper, the social apparatus—inextricably shapes the end "result" we contemplate today, proving the supposed objectivity a myth.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.