drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

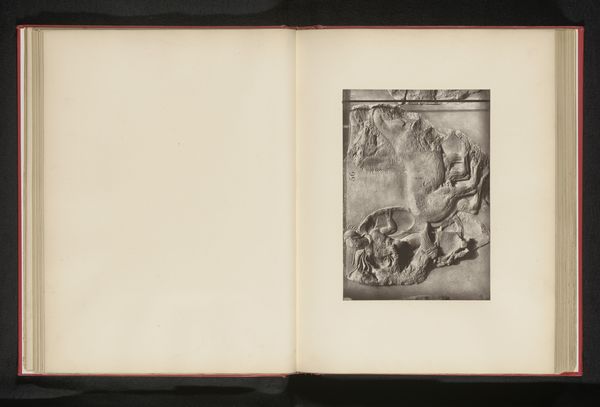

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil

#

nude

Dimensions: height 70 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

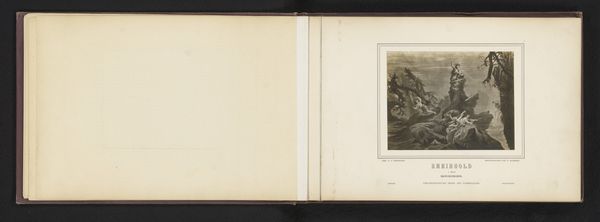

Editor: So, this is a photographic reproduction of a drawing of a putto – a chubby, male child, often nude, often winged. The original drawing, which this reproduces, predates 1876, and this copy lives at the Rijksmuseum. It's rendered in pencil on paper. The drawing has an almost melancholy air to it; the putto seems…off somehow, despite its classical origins. What's your take on it? Curator: Interesting. It's essential to consider how reproductive technologies like photography shaped art's accessibility and reception during the 19th century. Reproductions democratized imagery, but they also altered the original artwork's context and meaning. Was this reproduction intended for study? Or popular consumption? Editor: That's a good question! Given it’s bound in what appears to be a book, my hunch is the intent here might have been educational. The image seems more about conveying artistic knowledge. Curator: Exactly. It’s highly probable that this photograph served to circulate Renaissance artistic ideals, fitting into broader movements for artistic revival. Putti themselves, common in Renaissance art, symbolize innocence and divine love. In what ways do you see these symbolic meanings present, or perhaps challenged, within the reproduced image? Editor: I can see how Renaissance artists celebrated childhood. But this version almost has a gravity that's contradictory, maybe because of its form as a reproduction in a book. I’m not seeing divine love in *this* child, but something more serious. Curator: I think that perhaps its presence in a book, a signifier of knowledge and erudition, imbues the image with that feeling of sobriety you detected. Also consider the power dynamics at play when an institution like the Rijksmuseum collects and displays reproductions. Whose narrative is being amplified, and potentially, whose is being overlooked? Editor: That's a very good point. I didn't even think about it in terms of institutional power and narrative control! It makes you wonder what other art historical images are framed for the public and to what end. Curator: Exactly, it is important to always remember context and agenda, which allows you to interpret work much more broadly than you had originally imagined.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.