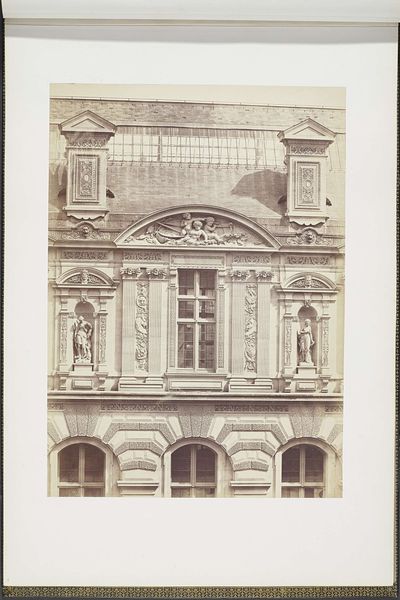

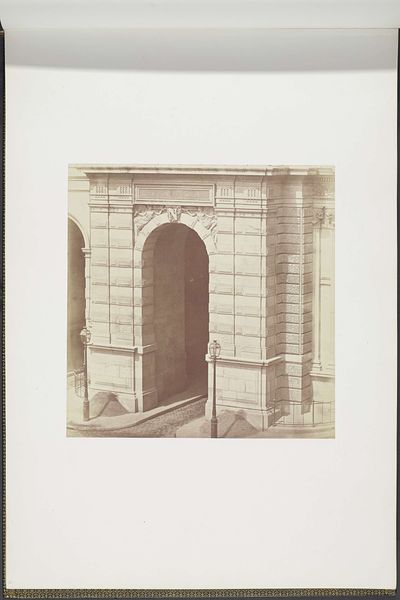

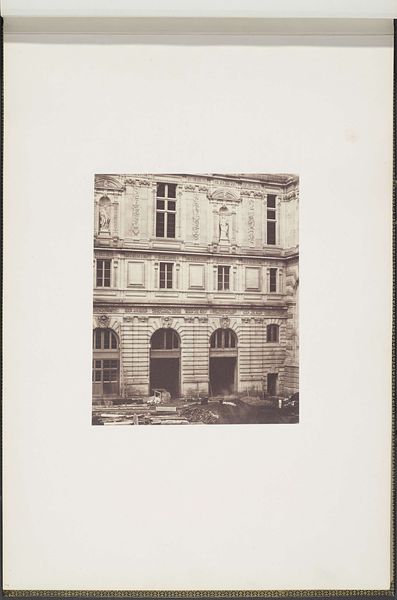

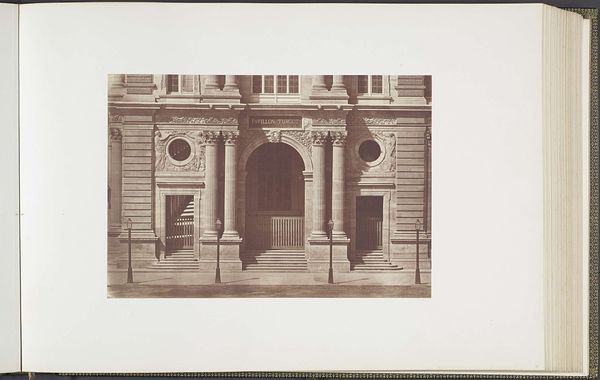

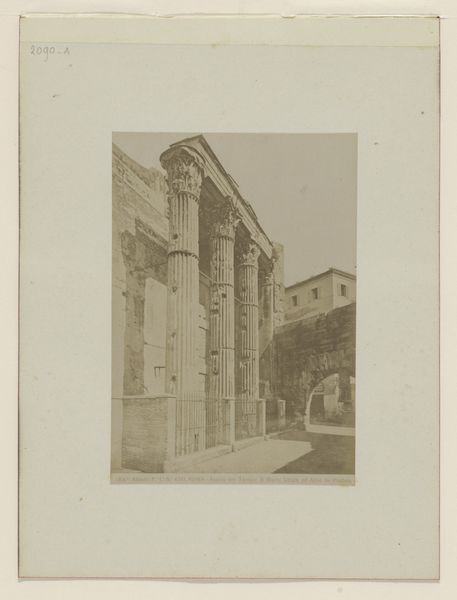

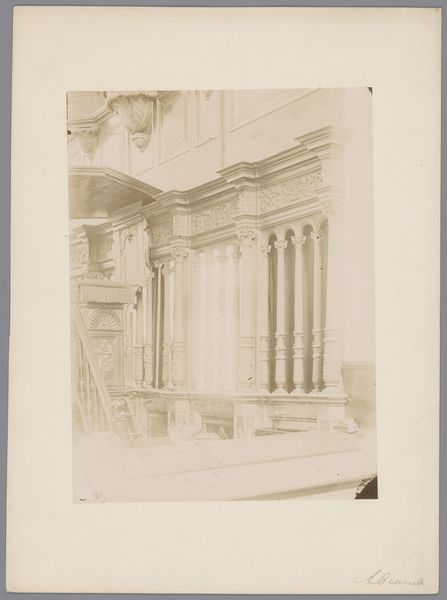

Gipsmodel voor een versiering op het Palais du Louvre door Jean-Pierre Hurpin en Marie Etienne Cousseau c. 1855 - 1857

0:00

0:00

edouardbaldus

Rijksmuseum

print, found-object, photography, sculpture

#

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

incomplete sketchy

#

hand drawn type

#

classical-realism

#

found-object

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

tonal art

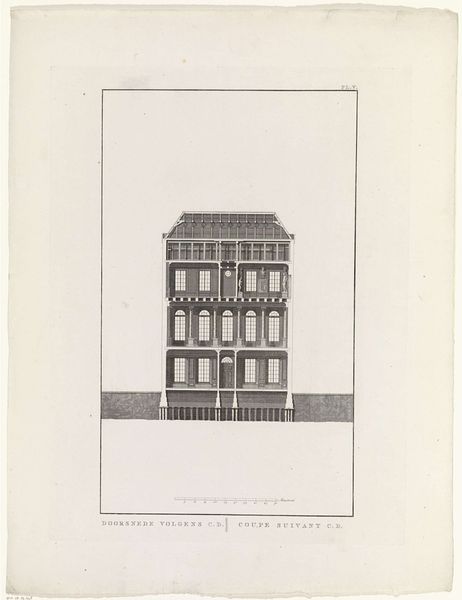

Dimensions: height 378 mm, width 556 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

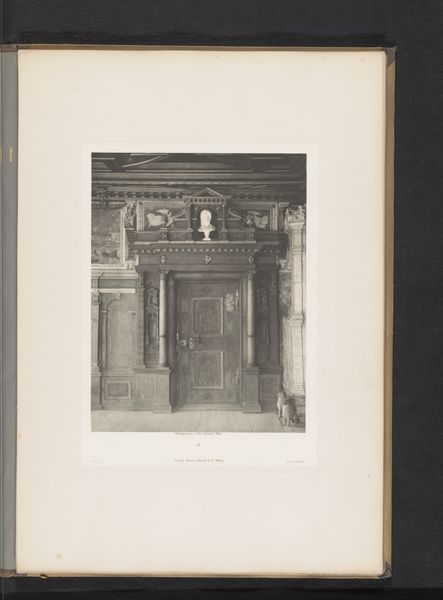

Editor: Here we have a photograph titled "Gipsmodel voor een versiering op het Palais du Louvre door Jean-Pierre Hurpin en Marie Etienne Cousseau," created around 1855-1857. It depicts a plaster model. The sepia tone gives it a sort of antiquated, bureaucratic feel. What stands out to you about this piece? Curator: I'm struck by how this photograph invites us to consider the relationship between art, power, and labor in 19th-century France. It's not just a simple documentation of a plaster model; it speaks to the vast, often unseen, network of artisans involved in the construction and embellishment of iconic symbols of state power, like the Louvre. How were sculptors Hurpin and Cousseau implicated in the visual language of empire and authority? Editor: That's interesting, I was really just thinking of it as a record of a sculpture! How do we unpack that implication? Curator: Well, think about neoclassicism, the dominant style at the time. It draws heavily from ancient Greece and Rome, associating the French state with those historical empires and their supposedly "natural" right to rule. Also, this photograph, presented almost as an archival document, enforces a certain official narrative and begs the question, whose stories and labor are deemed worthy of preservation and recognition? What social hierarchies are embedded within the very act of photographing and archiving? Editor: So, seeing it as more than just a photo reveals those hidden layers of meaning. Curator: Precisely! It allows us to question the supposed neutrality of art and recognize its active role in shaping perceptions of power and social order, then and now. It also speaks to how collaborative art can be and still overlook those that contribute to it. Editor: This has given me a lot to consider regarding what it meant to work on art back then. Curator: Exactly, and thinking intersectionally enables us to look at any artwork in a new way!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.