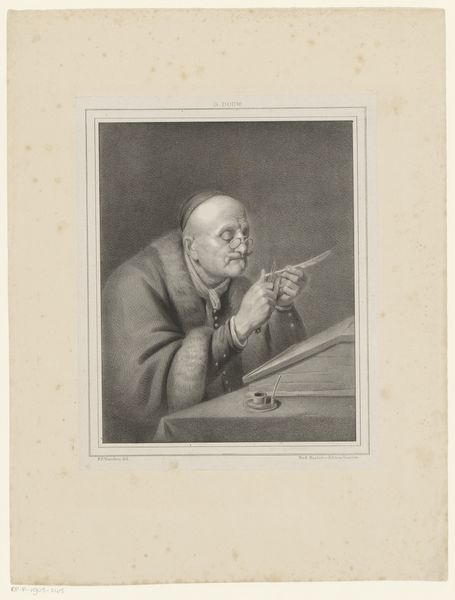

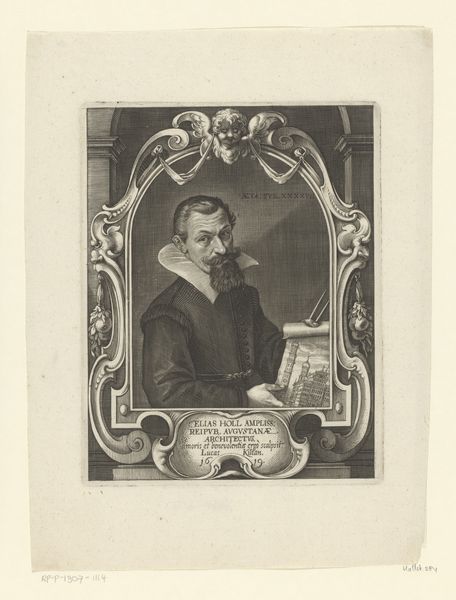

Dimensions: height 435 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

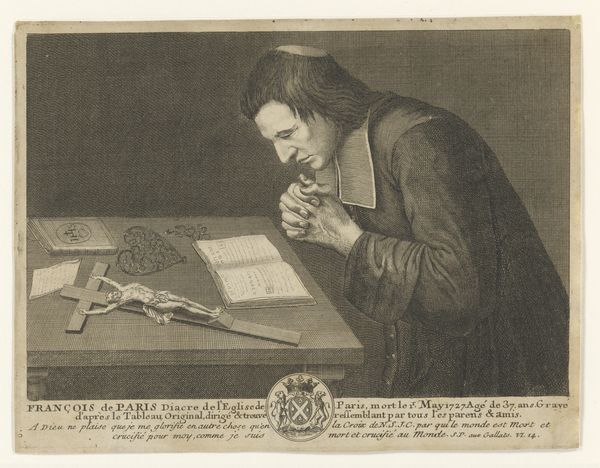

Curator: Looking at this somber figure hunched over his worktable, I can't help but feel a sense of intense focus and quiet contemplation. It almost feels hermetic. Editor: This is a print from 1762, attributed to Christian von Mechel, titled “Portret van Nostradamus," residing here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s an engraving done in a precise, linear style characteristic of its period, wouldn't you agree? Curator: Definitely linear, but more than that. Considering what Nostradamus signifies in popular imagination – as this sort of liminal, oracular figure – I’m interested in what his rendering suggests about shifts in power as related to systems of knowledge and meaning-making in the 18th century. Editor: You’ve made me think of the broader cultural context for these types of portraits, placing Nostradamus, as an intellectual figure, within a burgeoning culture of scientific inquiry and perhaps away from purely divine explanations for things. Curator: Precisely. Here we have Nostradamus, but there’s an empiricism implied by his focus on instruments, books, maybe an hourglass. It speaks to an interest in human action and explanation, less about predetermination from forces beyond ourselves. In this portrayal, it all exists as tangible, touchable items on his desk. Editor: That's a key shift: this engraving is a testament to how perceptions of even mystical figures were being reshaped. You can consider the print as a political object: an artist consciously working to legitimize the shift toward the Enlightenment, aligning historical figures, even ones with a dubious provenance, with this new, material-based rationality. Curator: It highlights art's complex dance with both perpetuating dominant narratives and pushing for reformative social changes. And I do wonder what messages such art conveyed about intellectual credibility, then as now. It definitely merits more study to be able to tease apart that. Editor: Well said. It's always fascinating how seemingly simple portraits can reveal intricate webs of meaning tied to the public and the politics of image-making during a specific era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.