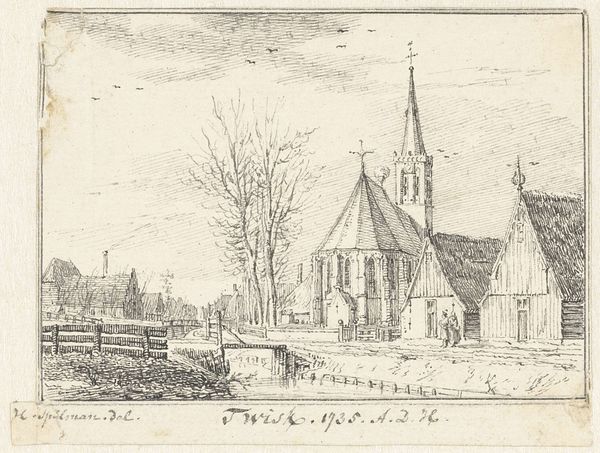

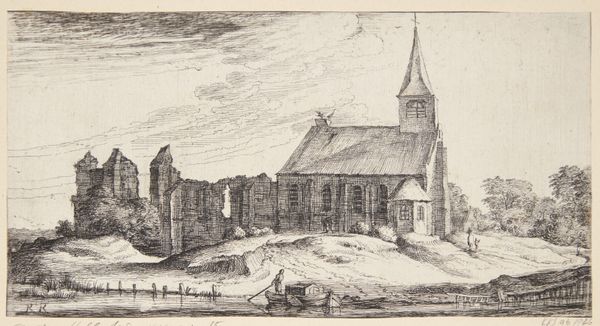

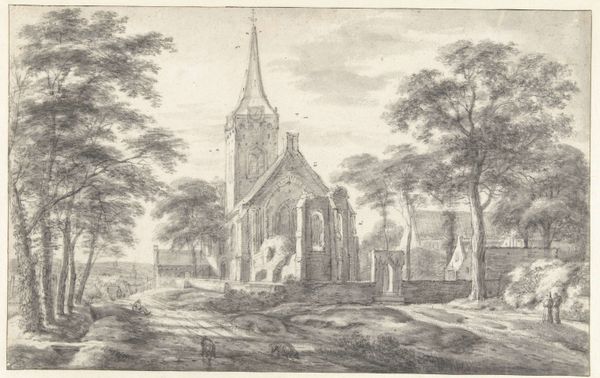

drawing, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 143 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this evocative scene, "Kerk te Sloterdijk," dating back to 1607, etched by Claes Jansz. Visscher. It’s an ink and etching on paper. Editor: It’s haunting. There's a profound sense of quiet melancholy about this depiction of the church, softened by what seems like the Dutch light even rendered in monochrome. Curator: I am curious about your use of “haunting”. The artwork emerged during a period of religious and political upheaval in the Netherlands; how might those tensions seep into our viewing experience? Editor: Perhaps in the stark simplicity. The church feels isolated, vulnerable even. The buildings around it are modest, but then again, its humble character may well reflect Dutch Protestant values rejecting opulent religious architecture. It would then underscore communal life more broadly. Curator: Absolutely. Visscher uses landscape, a dominant style in the Baroque, not as a mere backdrop but as a political stage. We’re seeing not just a place, but a community’s values enshrined, their act of defiance, perhaps even their act of conformity made to stand for generations. Editor: It also features such precise, meticulous line work, so typical of Visscher. The etched lines aren't just defining forms; they're suggesting textures and qualities of light that communicate the very spirit of the time. These choices have psychological heft. The linear character itself represents puritanical mores or maybe new capitalist pathways to rationality, eh? Curator: Fascinating connection to capitalist pathways, something not frequently evoked in the art history of this era, but completely reasonable considering its rise alongside this church as an emblem. Visscher situates himself in a period ripe with burgeoning colonial influence and devastating inequality. Editor: This etching’s not simply a rendering; it is an imprint of that critical juncture, reminding us how social histories sediment within even the most "objective" seeming art, in an otherwise tranquil village church. Curator: The etching challenges us to reconsider the relationship between place, power, and piety and even to draw our attention to our inherited complicities. Editor: And as we depart, what might we consider to be the iconographic implications for modern church visitors of secular images like this one? Curator: It's a reminder that how we frame faith and the stories of community determines what those practices come to be in new historical horizons.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.