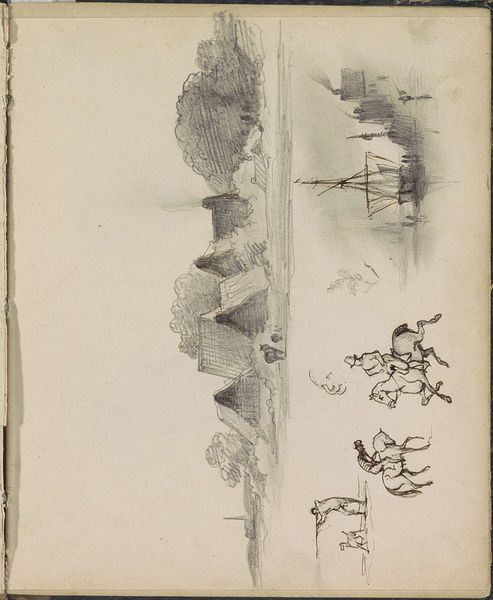

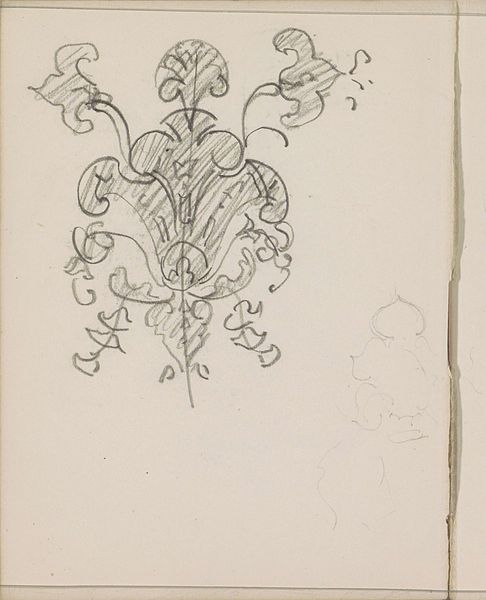

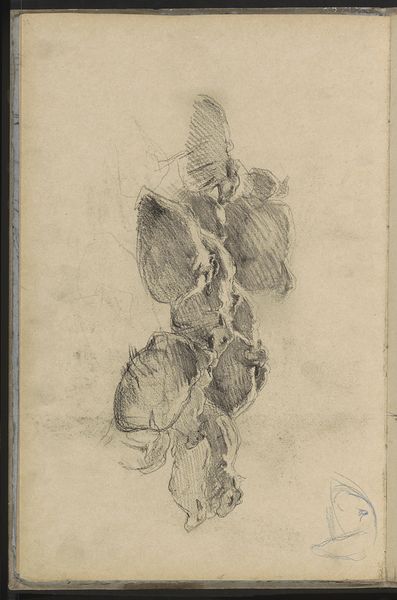

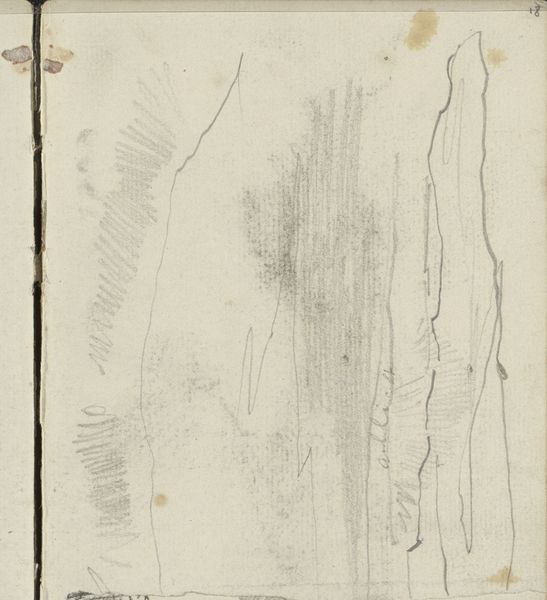

drawing, paper, pencil

#

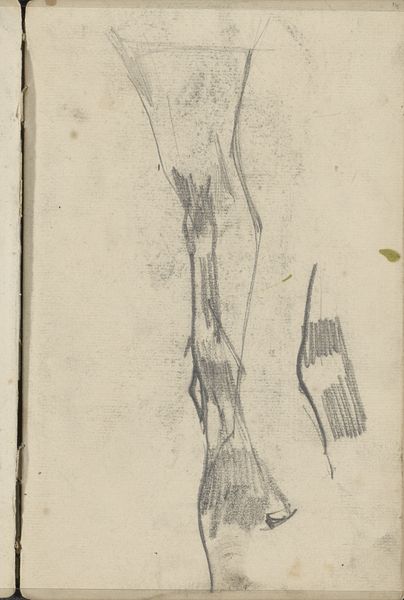

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

art-nouveau

#

pencil sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Ornamenten," a drawing by Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof from around 1901. It's on paper, with pencil, and looks like a page from a sketchbook. It has a very light and airy quality to it, almost ephemeral. What strikes you most about this work? Curator: I see a yearning for freedom struggling within the confines of tradition. Art Nouveau, while visually stunning, often reinforced societal expectations around domesticity and idealized nature, particularly for women. Do you think Dijsselhof’s choice of such light lines might suggest a resistance to these more rigid expectations? Editor: That's a really interesting point! I hadn’t considered the restrictions of Art Nouveau. The tentative nature of the lines could be interpreted as questioning those norms, rather than fully embracing them. It's almost like he's sketching out possibilities, unsure of what he wants to commit to. Curator: Precisely! And it raises questions about who this "ornamentation" is actually *for*. Was it a decorative exercise detached from any specific application? Or were these designs intended to beautify objects or spaces within the domestic sphere, indirectly shaping the lives – and perhaps constraining the identities – of those inhabiting them? What is the politics of ornamentation, and who truly benefits? Editor: I guess I hadn’t really thought of ornamentation having politics, but I can definitely see what you mean now. I suppose anything that's designed to shape our environment also, in a way, shapes us. Curator: Exactly. This little sketch prompts us to consider art not as an isolated object, but as an active participant in the broader social and political landscape of its time – and, importantly, of our own. Editor: It really highlights the importance of looking beyond the surface. Thanks; that gives me a lot to think about!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.