print, engraving

# print

#

pen illustration

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: width 208 mm, height 87 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

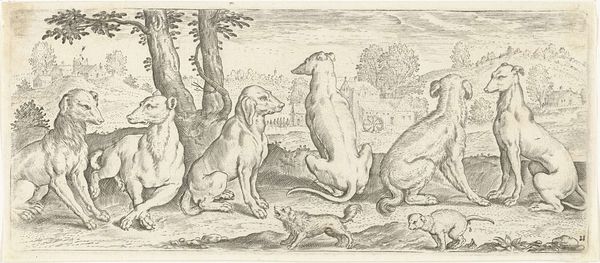

Curator: The work before us, created after 1583 by Abraham de Bruyn, is titled "Gazelle, olifant en neushoorn" – "Gazelle, Elephant and Rhinoceros". It's an engraving. What strikes you about it? Editor: Immediately, it’s the almost comical way these animals are rendered. There's a distinct sense of the artist working from descriptions rather than firsthand experience. They are standing so serenely as though posing. Curator: Exactly. De Bruyn, working in the Northern Renaissance style, likely never encountered these animals personally. Consider how Europeans perceived the exotic and monstrous; this print functions as a visual record, an almost anthropological study through the lens of artistic license. Editor: The clothing, though, on the Rhinoceros makes this less realistic, what can that mean? Curator: The inclusion of these features provides significant symbolism to its interpretation and purpose. Such a print serves a greater didactic purpose in conveying certain messages. It makes the piece not so foreign by incorporating clothing as an item to relate with. Editor: What strikes me is the flatness of the background versus the detail given to the animals in the foreground. The composition seems deliberately staged to showcase these beasts to an eager audience, but this doesn't diminish how it affected how the West came to understand the animal world. Curator: The artist's intent was to represent the “new” and unknown. The gazelle is common, whereas, in Early Modern Europe, to have the elephant or the rhinoceros displayed indicates prosperity and a global reach. As symbols, they carry significance related to power. Editor: Despite the factual inaccuracies, the gazelle stands out; its slender form and comparatively gentle expression evoke an undeniable emotional connection to innocence against a wild surrounding. This speaks volumes about the Renaissance interest in depicting "correctly" and with an interest in aesthetics that carry greater significance, even meaning. Curator: I agree; it showcases a crucial moment when Europe tried to visualize and classify its widening world, reflecting the period's burgeoning interest in natural history and the complex cultural meanings assigned to different animals. Editor: Indeed. De Bruyn's print leaves me contemplating how visual depictions of the "other" not only reflected but shaped perceptions during the Renaissance, leaving an undeniable cultural imprint to this day. Curator: I concur; through such seemingly simple depictions, cultural memory is formed. These images, however flawed, continue to echo through our shared imagination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.