photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

contemporary

#

black and white photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

environmental-art

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: image: 22.86 × 27.94 cm (9 × 11 in.) sheet: 27.94 × 35.56 cm (11 × 14 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

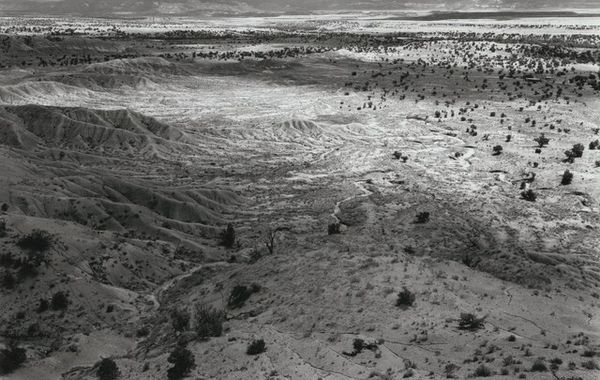

Curator: This is Robert Adams' "Alkali Lake, Albany County, Wyoming," a gelatin-silver print from 1977. It captures a seemingly unremarkable stretch of the American West. Editor: My first thought is the vastness. It's incredibly bleak, almost oppressively so. The horizon line is so high, the sky pressing down. The lake appears more like a stain, a wounded space. Curator: Adams, throughout his career, was deeply concerned with how the Western landscape was being altered by human intervention and development. This image exemplifies that concern. Editor: Visually, the flatness is striking. There's very little tonal variation. It's almost like a study in texture rather than form. See how the photographer utilizes the subtle changes in light across the landscape to create visual depth, albeit minimal. The way the sparse vegetation contrasts with the smooth surface of the lake; those juxtapositions pull me in. Curator: Precisely. It's a testament to Adams' critique of the "New West." Gone is the romanticism of Manifest Destiny; instead, he offers an unflinching look at the impact of settlement—of resource extraction and unchecked development. Think of it as a visual counter-narrative to traditional landscape photography. The banality underscores his point. Editor: It challenges the viewer's expectations, absolutely. The photograph lacks a focal point. The circular lake could be construed as one but really acts as a compositional pivot that maintains the circular and tonal qualities that emphasize flatness. The minimalist aesthetic and the gelatin silver print really reinforce that point. It forces you to consider every detail, every subtle gradation in tone and texture. Curator: I'd agree with you. The photograph serves as evidence—a document, if you will—of a changing social landscape and prompts us to think about our own role in these transformations. It reminds me of Walker Evans’s project of cataloging a vanishing America during the Great Depression. Adams is cataloging another vanishing America, this one succumbing to its own perceived progress. Editor: It’s interesting how such a seemingly straightforward image invites such layered readings. I find the success of its formal choices especially compelling. Curator: Adams makes us reckon with uncomfortable truths about progress and its consequences.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.