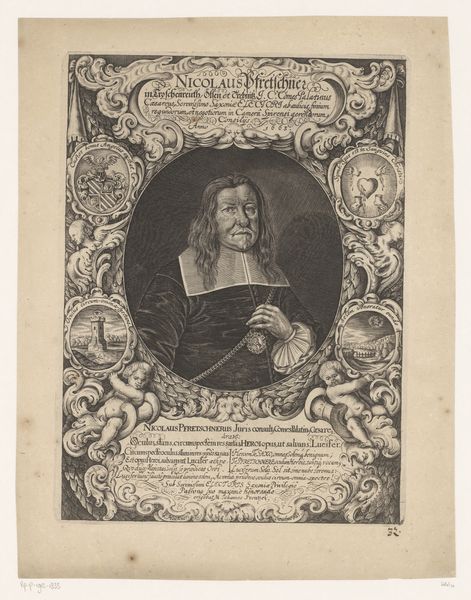

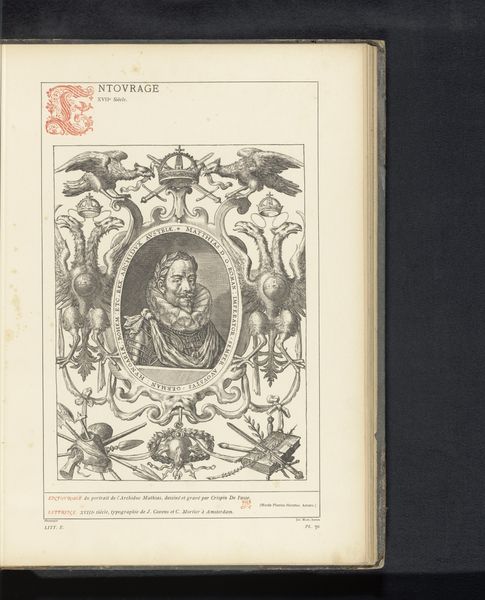

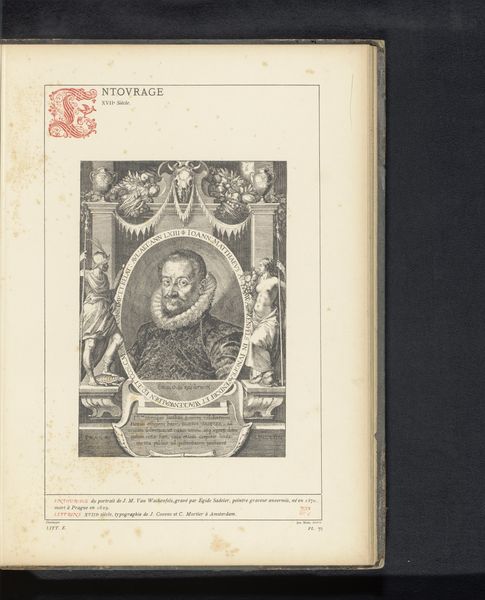

Reproductie van een prent van een portret van keizer Ferdinand III door Pieter de Jode I naar Anselm van Hulle before 1880

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 316 mm, width 231 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

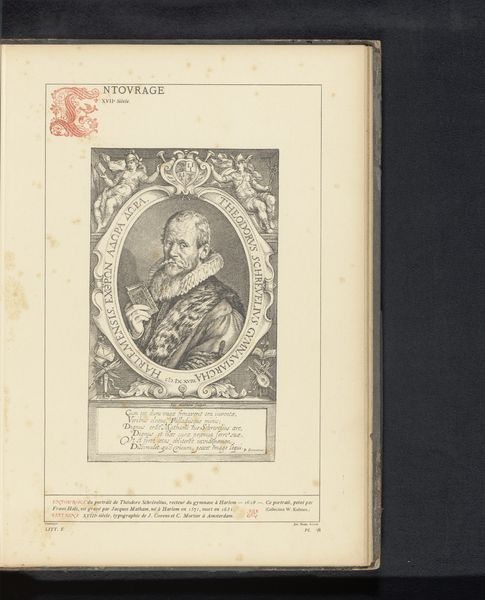

Curator: My eye's immediately drawn to the contrast—a stern portrait framed by such lavish, almost cartoonish ornamentation. Is it just me, or does that mismatch feel kind of... cheeky? Editor: Well, this cheeky juxtaposition frames a reproduction of an engraving, dating from before 1880, portraying Emperor Ferdinand III. The original engraving was created by Pieter de Jode I, who worked from a design by Anselm van Hulle. Curator: Ah, Ferdinand, caught in a whirlwind of baroque embellishments! Those trumpets almost overshadow him. Who decided that such somber portraits needed all that fuss? Editor: Remember the function of portraiture at the time: legitimacy and power. Engravings such as these were produced and disseminated to maintain visibility, a sort of pre-modern media campaign ensuring a consistent image was available for various public spheres. The setting is therefore highly constructed, very conscious, an attempt to impress. Curator: So it's propaganda then! And to think he just looks like a man who'd rather be tending his roses. Still, there's a vulnerability in those eyes that escapes the pomp and circumstance, you know? It's as if the artist was saying, "Yeah, he's an Emperor, but also…just a guy." Editor: An intriguing point! The success of baroque portraiture resides in its dual function; the representation of authority whilst offering the tantalizing semblance of individual likeness. A paradox in painted form. The face retains character. Curator: Precisely! It's the artist subtly sabotaging the Emperor’s perfect image, almost whispering, “Don’t be fooled by the crown”. Editor: Perhaps not sabotage. Rather a necessary compromise between subject, artist, and the demands of representing imperial authority. And that compromise, visible still centuries later, adds layers to the portrait that would be lost otherwise. Curator: Compromise then? Either way, it adds spice to what might have otherwise been just another stuffy portrait. It makes me think about who *we* choose to immortalize and how. What story will those portraits tell generations from now? Editor: An excellent thought on which to conclude, because if art serves as a mirror to society, it also presents a lens for examining our present and our values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.