#

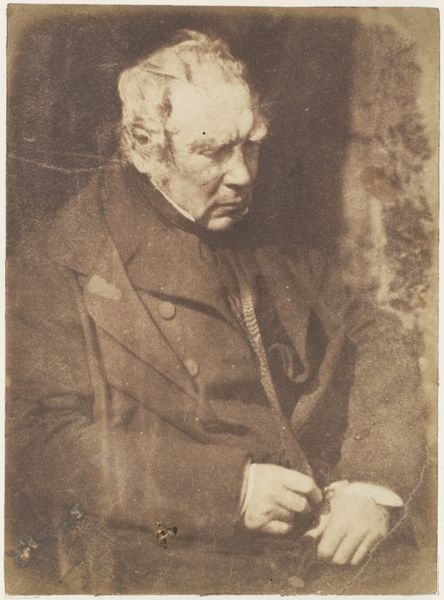

portrait

#

wedding photograph

#

photo restoration

#

low key portrait

#

charcoal drawing

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

strong emotion

#

single portrait

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

celebrity portrait

Copyright: Public Domain

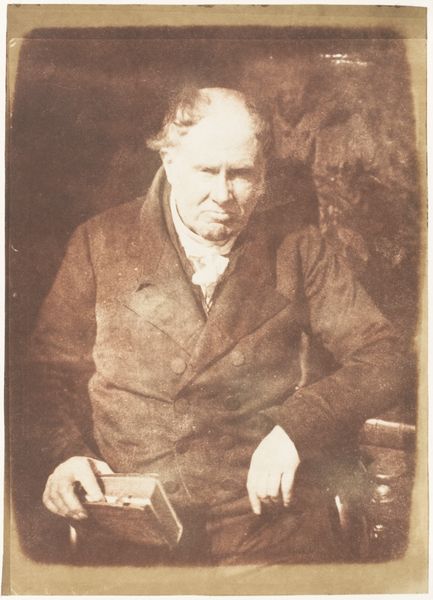

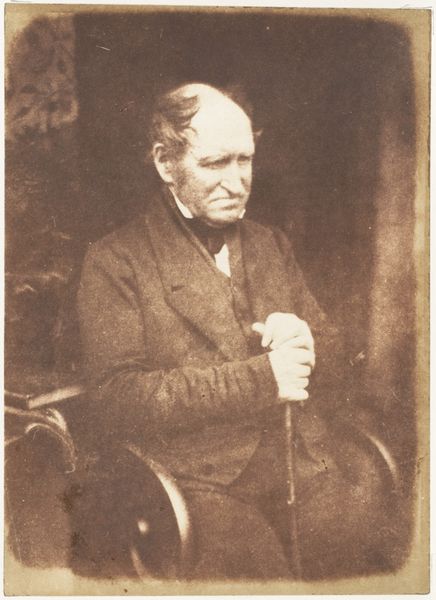

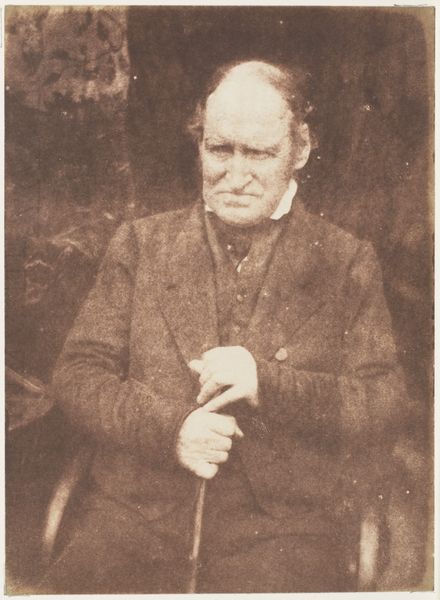

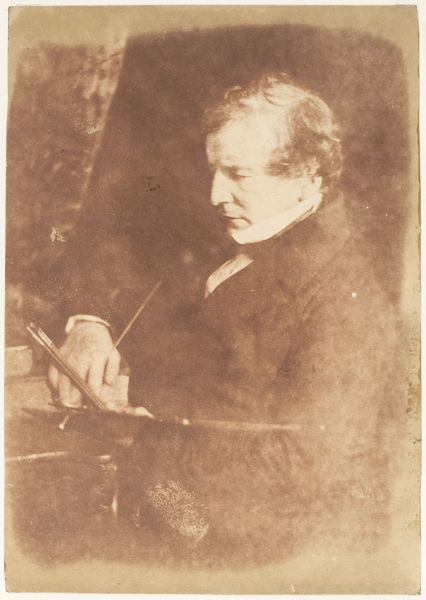

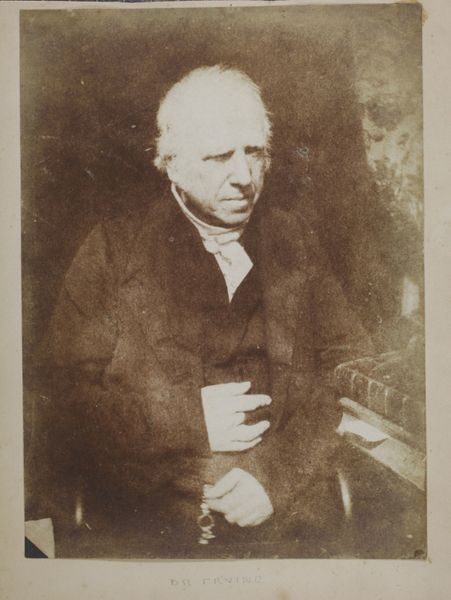

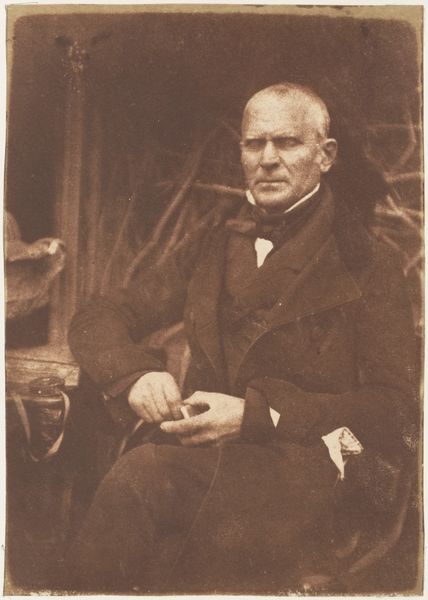

Curator: This remarkable calotype, "Dr. Cook of St. Andrews," was created sometime between 1843 and 1847 by the pioneering Scottish photographers, David Hill and Robert Adamson. Editor: It's strikingly somber, isn’t it? The muted tones lend a certain gravity to the image, and his gaze…it suggests a deep introspection. Curator: Indeed. Hill and Adamson were masters of using light and shadow to convey character. But the calotype process itself— a negative image on paper—was still quite new at this time. They captured something almost painterly here. Consider that Dr. Cook was a prominent figure in the Church of Scotland during a very tumultuous time of schism and religious debate. Editor: Yes, I notice how the very lack of sharp detail makes it feel timeless, almost allegorical. Is he holding something? It seems significant but unclear. I also wonder how aware Cook was of the impact that photographs have. Was he intentionally staging a public image here? Curator: He is holding a book. The placement, near the edge, suggests knowledge. But given the context of the time, it could also signify commitment to theology. As for his awareness, photography at this point in history had an evolving social presence. This photo comes not long after Louis Daguerre invented the daguerrotype, with its association of realism, so to move from such specificity into this soft, almost spiritual form may have appealed to him. These photographic portraits of such figures served a crucial function: visually constructing and reinforcing a particular cultural narrative of intellectual and religious authority. Editor: I think what really holds my gaze is that soft focus. It gives such prominence to his face, a real study of contemplation that almost transcends photography itself and touches a level of universal thought, of scholarly solemnity, far removed from today’s constant photo documenting and oversharing. Curator: And to see it now in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum, we're confronted not just with an individual likeness but a relic of social and cultural history, a testament to how we choose to remember figures from the past, in this moment we call the present. Editor: A poignant glimpse into a world undergoing rapid change, captured with a technique still finding its feet. It prompts so many questions about permanence and the role of imagery in defining our understanding of legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.